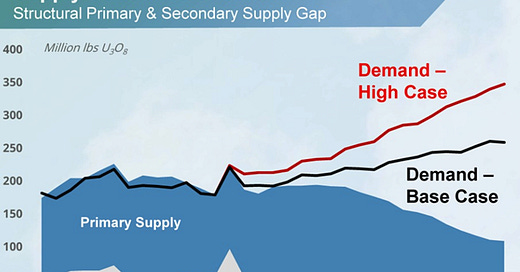

After the sideways chop in 2022 and the sharp draw downs in the first quarter of 2023, many are throwing in the towel on the uranium thesis. I have a different view, which I have shared several times on this blog - most recently in January. Volatility can be a means of transferring wealth from the impatient to the patient, and I think that’s what’s happening here. Below are some of the key questions skeptics are asking and what I think they’re missing.

Why Aren’t Prices Moving Faster?

The first question most investors new to the sector ask is why uranium prices aren’t shooting higher when the market is in deficit. The answer lies in the nature of the fuel cycle, term contracting and spot market dynamics, which are very different from traditional commodities. These are complex topics and if you’re not willing to do the work to understand the nuances of how this opaque market functions, you’re unlikely to develop the conviction necessary to hold through the volatility.

Most uranium purchasing (80%+) happens in the term markets. Utilities sign long term (LT) 5-10+ year contracts with uranium miners (the details of which are usually covered under an NDA and not released to the public) and then renew these contracts as they approach maturity. Most utilities don’t wait until the last minute to renew. If a power plant has less than 2-3 years of inventory remaining, they’re likely going to be in the market for new contracts. This is not an industry where you can get away with just-in-time inventory, for obvious reasons. This means that even when the market falls into deficit, the reaction to prices happens with a lag as utilities are typically sitting on a couple of years of inventory, which they can continue to draw down before they really need to buy more.

Over the past several years, utilities have been contracting at well below the rate required to replace their future annual requirements. The reason is that they have been told for almost a decade that there is no shortage of uranium, and until recently this was true. Some of the older nuclear plant operators were also expecting that they may have to shut down their reactors permanently, so it didn’t make sense for those reactors to purchase fuel for the long-term. As a result, term contracting volumes have remained anemic since 2013. 2022 was the first year since 2012 that term contracting volumes broke above the 100mm lbs mark, and this is still well below global annual requirements (~185mm lbs).

In summary, utilities have been contracting at well below replacement rates for almost a decade because prices were low, inventories were high and there was a lot of political uncertainty regarding the future of the nuclear industry. We are in a very different market today. The pick up in contracting volumes in 2022 is a sign that utilities are starting to wake up. The widening acceptance of nuclear as a green energy source has made the existing supply / demand deficit acute.

The nuclear production tax credit under the Inflation Reduction Act and countless reactor life extensions globally mean that utilities that were previously unsure about the future of their nuclear plant fleet can now buy fuel with confidence. Reactor restarts in Japan mean that overhang from Japanese inventory has disappeared. Finally, the push towards both conventional and advanced (SMR) new-builds in order to meet future global energy needs continues to gain momentum, with new projects being announced pretty much every week.

Given all of the above, it’s reasonable to ask why utilities aren’t panicking and trying to secure as many pounds today as possible. The answer is that utilities are bureaucratic organizations that move slowly. They are also prone to herd behavior and closely monitor what their peers are doing. In other words, they move slowly but when they do, they move all at once. In the nuclear fuel space, contracting begets more contracting and that cycle has already started with the big pick up in 2022 volumes. Cameco CFO, Grant Isaac, recently described it this way: "Utilities can defer and they can delay, but they cannot ultimately avoid the need to procure this material" (referring to utilities uncovered requirements going into the next decade).

Though it’s still early in the year, 2023 YTD contracting is ~50+mm lbs, annualizing to >200mm bls. If this rate of contracting persists, it’s inevitable that uranium prices will rise up, and possibly sharply.

The last point I’ll make on this topic is that price reporting in the industry does not make it any easier for investors to assess the health of the market. For example, the term market price, as determined by industry consultant UxC, is based on the lowest offer in the market during the reporting period (monthly). The bulk of the LT contracts currently being entered into are in the high $50s per pound and higher, yet because there may be one LT contract being offered in the low $50s, that is the price that UxC reports. The LT contract price is the most important pricing information in the uranium sector as it reflects the majority of uranium purchasing and determines the profitability of uranium mining companies, yet its reporting methodology is severely flawed.

How Much Inventory Is Out There?

A number of bull thesis skeptics have pointed out that there are ‘billions of pounds of uranium inventory out there’ and that there is in fact no shortage of uranium. Because uranium inventory figures are also opaque, it’s hard to refute the excess inventory argument with real-time inventory data. But a simple rebuttal to this argument is to point to the steady upward trajectory in uranium prices over the past few years. If there was indeed so much excess inventory, why would utilities be signing contracts in the high $50s and even $60s vs. a $20 - $30 uranium price a couple of years ago?

The more detailed answer is to look at where inventory resides globally and its purpose. Industry experts like Dustin Garrow, Managing Principal at Nuclear Fuel Associates (which provides brokerage, trading, marketing/sales services to the nuclear fuel industry), and Per Jander, Director at WMC Energy (another nuclear fuel broker), who have been involved with nuclear fuel trading and brokerage for many decades, have the following observations to make on uranium inventories:

Based on several estimates, total uranium inventories are roughly ~1 - 1.5bn lbs globally, this is down from 2bn lbs historically (a lot of it was held by Russians).

This might seem like a very large figure, enough to cover many years of global consumption, but once we start to categorize the inventory it becomes more clear that this is not the correct interpretation of these figures:

Around 250mm lbs of inventory (~18 mos of global demand) are typically in the ‘fuel building’ / ‘in-process category’, meaning that these are inventories already under contract and being readied for fuel fabrication / future consumption. Some is held by enrichment and conversion facilities. We can call this ‘working inventory’.

Strategic inventory: When Japan was operating 55 reactors consuming 20mm lbs per year, they wanted a minimum of 4 years / 80mm lbs of inventory in reserve. Similarly, most utilities today hold 2-3 years of consumption as a precautionary measure / margin of safety which equates to 400 - 500mm+ lbs. This number could go up if utilities feel insecure about future supplies.

~500mm+ lbs of inventory resides in China. This may seem excessive in relation to China’s current consumption, but not when you factor in the country’s plans to build 150+ reactors over the next 15 years. Also important to note is that when new reactors come online, preparing the initial core requires 2-3x the reactor’s annual fuel consumption. Some of the larger reactors coming online in China require 2mm lbs upfront to load the initial core.

During the 2022 World Nuclear Association Symposium, the following comments were made by various industry participants about the inventory situation:

UxC: The era of excess inventories overhanging the nuclear fuel market is “emphatically behind us”. There is very little mobile inventory left in the market and the majority is held by financials, utilities and other suppliers who have sequestered inventory for the long term. Utilities who could previously buy inventories from a flooded spot market will now be unable to do so. Those seeking security of supply will need to begin contracting soon.

Findings from UxC’s 2022 Global Nuclear Fuel Inventories (GNFI) report concluded that the trend of inventory reduction that began in 2017 has continued over the last few years, and accelerated by several factors - primarily the emergence of financial entities such as the Sprott Physical Uranium Trust (SPUT) which have sequestered millions of pounds of uranium from the market for the long term.

During the 2020 - 2022 period inventories at financial entities increased 140%, while US, EU, Japanese and uranium trader inventories all declined significantly.

Laurent Odeh, CCO of Urenco (enrichment services provider): “Post-Fukushima, we had high levels of inventory in the market which provided flexibility… that flexibility is now gone”.

Agnieszka Kazmiercak, Director General of Euratom Supply Agency: “We need commitment from customers. Everybody needs to look further. There is a lot of hesitation and unwillingness to commit.. the users [of nuclear fuel] need to play a more prominent role in looking forward and understanding our new reality”.

To conclude, while there is significant uranium inventory globally, this inventory cannot be viewed as ‘mobile’ or ‘excess’ inventory that can be used to meet incremental uranium needs.

When Will The Spot Market Move?

Despite the much smaller size and relative importance of the spot market, many investors remain fixated on spot price because it’s the only uranium price updated on a daily basis and highly visible to the public. In 2021 the spot market made a big move upwards when SPUT was consistently trading at a premium to NAV and raising capital to buy more pounds. However, since then the macro environment / capital market sentiment has deteriorated in response to inflation and interest rate hikes. Buying pressure from SPUT has abated and the spot market has trended sideways.

One of the important dynamics to understand about the spot market is that it acts as a liquidity source for price-insensitive uranium sellers. There are roughly 20-25mm lbs / year of uranium that are sold in the spot market by: 1/ producers that produce uranium as a by-product to their main operations 2/ brokers and traders with excess inventory 3/ miners / developers looking to cover their cash operating costs.

For example Olympic Dam mine owned by BHP is the world’s fourth largest copper deposit, but it also produces some uranium, which makes its way into the spot market. BHP doesn’t have the sales / marketing infrastructure in place to sell these pounds through negotiated long term contracts with utilities so this supply gets ‘dumped’ in the spot market. Other examples of price-insensitive sellers include Uranium One, African JV partners, Itochu (Japanese nuclear fuel broker with long-term purchase contracts from Uzbekistan), etc.

While this ~20-25mm lbs / year of supply in the spot market is inelastic / constant, demand in the spot market is erratic and hard to predict. The physical uranium trusts only show up in the market when broader financial markets are doing well. Utilities buy most of their fuel through LT contracts and only dip into the spot market on an ad-hoc / opportunistic basis. This means that sellers in the spot market are typically price-takers, buyers are price-makers. Hence, the spot market often trades at a lower price than dictated by the pure supply / demand fundamentals.

There are a few catalysts on the horizon though that are likely to change this dynamic and lead to a significant upward pressure on spot prices going forward:

Kazatomprom (KAP), the world’s largest uranium producer, guided to 2023 production being 4 - 5mm lbs lower than anticipated; if production levels in Kazakhstan fail to meet expectations, KAP and other producers in the region like Cameco, Orano etc may have to buy more uranium in the spot market to meet delivery requirements under LT contracts with their customers.

100% of Uranium One’s production comes from JVs in Kazakhstan, which could mean less spot selling by Uranium One this year.

As positive sentiment towards uranium continues to build and financial demand for uranium increases, eventually spot purchasing from physical trusts will return and overwhelm the supply:

For example, Yellow Cake has an option to buy 1.5mm lbs of uranium from Kazatomprom (KAP), which KAP may need to buy from the spot market given its lowered production guidance.

ANU Energy is looking to raise $500mm ($100mm private placement in Q2 2023 and $400mm IPO later in the year) to buy physical uranium from Kazatomprom; again these are pounds that will likely have to be sold from KAP’s strategic reserves / inventory and replaced through spot market buying.

John Ciampaglia (CEO of SPUT): "We saw a noticeable pickup of interest at the start of 2023, from both existing as well as new investors. We have seen a sea change in the level of interest from institutions."

Western underfeeding is going away, which means the loss of 15 - 20mm lbs / year of secondary supply (if you are not familiar with the concept of under / over feeding, read my fuel cycle primer here). Some enrichers have committed to delivering this secondary supply to utilities in the future and will now have to either renege on those agreements, or buy the missing uranium from somewhere else. Either way, the loss of secondary supply will increase pressure on spot market purchasing.

The switch to overfeeding means that enrichers will need more uranium going forward than what is covered under their existing LT contracts (which were signed during a period of underfeeding). The balance of the uranium demand will have to be met from somewhere else, and could very well be the spot market. The first leg of this process will be diminishing UF6 inventories, which will then lead to UF6 re-stocking, requiring more U308.

The pressure on UF6 inventories can already be evidenced through the sharp rally in spot conversion and UF6 last year.

UF6 re-stocking will accelerate in 2023 with Converdyn / Metropolis restart.

Carry traders that sold pounds in 2021 to take advantage of a backwardated market will need to replace those sold pounds to honor their contracts to supply fuel in 2022 - 2024. Most of this demand will be met through LT contracts with producers, but some may have to be met in the spot market.

Many LT contracts with utilities have ‘flex’ provisions allowing the utility to purchase +/- 10 - 20% more / less uranium vs. the base amount, at the utility’s option. As supply insecurity increases, utilities may start exercising this option to ‘flex up’ their purchase volumes. Producers may struggle to meet this additional demand from primary production, forcing them to buy pounds in the spot market.

As term contracting picks up and utilities start contracting at >100% of their requirements, they will inevitably need to dip their toes into the spot market as there is simply not enough primary supply under LT contracts available.

Bringing this all together, there are many forces in play currently that could push the spot market higher but their timing is hard to predict. Investors who are myopically focused on spot prices are missing the bigger picture of tectonic shifts happening in the term contracting market and several elements of the fuel cycle.

It’s important to note that despite all the financial market volatility over the past few weeks, spot prices have remained firm at $50 / lb and are slowly grinding higher despite any purchasing from SPUT. The explanation, as confirmed by several industry sources, is that utilities have been buying uranium in the spot market opportunistically. As the supply / demand deficit further crystallizes, spot market activity and prices will face upward pressures.

Summary

There are a lot of uninformed takes and false narratives regarding the uranium market that are gaining traction in the financial community because of the lack of positive movement in uranium equities

Playing the uranium thesis requires a high level of patience and strong fundamental understanding of how the fuel cycle works, how uranium purchasing takes place and how price discovery works - the uranium market is more complex and opaque than traditional commodity markets

Uranium prices are moving up (LT contracts), just not the prices that investors are myopically focused on

Uranium inventories are not one, big monolithic body; categorizing the inventory and understanding where it sits and for what purpose is critical in developing a better / more complete understanding of the market

There are several pressures building in the spot market, but the timing of the impacts is hard to predict and often doesn’t match investor expectations / time horizons

If you can focus on only one variable / data point in the sector, it should be term contracting volumes; ultimately the supply / demand deficit will be crystallized by a pick up in utility contracting above available primary supply, pressuring both the term contracting and spot markets

Excellent my friend! thanks!

Fantastic piece!

(as always)