Good morning from sunny Miami. As I bask in the sunlight here (generated by nuclear power of course) and think about uranium sector outperformance this year so far, it’s hard not to reflect on where the thesis stands today. When I first researched and started allocating to the uranium sector, I’d never imagined that:

Japanese reactors would restart at the pace currently scheduled

The world would approve so many reactor life extensions

The US government would provide a production tax credit to nuclear reactors and the DOE would create a domestic uranium reserve

Western enrichers would switch from underfeeding to overfeeding

Small modular reactors (SMR) would go from being a concept to reality

Cameco would make a big acquisition supported by Brookfield as an anchor investor

The world’s largest uranium producer (Kazatomprom) would miss 2022 production estimates and guide 2023 estimates 4-5mm lbs lower

I could go on… but here we are.

The Russian invasion of Ukraine did two very important things to the uranium market: 1/ it brought energy security and independence front and center for all nations 2/ it bifurcated the market into East and West.

Due to energy security concerns, more and more countries are deciding to keep their nuclear reactors operational and even expand their nuclear fleet. Germany is a great case study of what not to do with your country’s power mix: after shutting down its nuclear power plants and spending more than half a trillion on wind and solar, the country’s electricity prices and CO2 emissions have exploded due to the intermittency of renewables and the constant need to rely on backup natural gas and coal generation. Similarly, after shutting off its reactor fleet after the 2011 Fukushima incident, Japan has been at the mercy of the global LNG and coal markets. With fossil fuel prices skyrocketing last year and the country’s commitment to reduce emissions, the Japanese government has made it a priority to restart its nuclear fleet and even expand it over time to contribute 20-22% of the nation’s power by 2030.

For many years world leaders demonized the nuclear sector and pushed the world down the ruinous path of overinvesting in renewables. Anyone who’s studied basic physics and understands the concept of energy density could have seen this trend backfiring in the long-term. However, as is often the case, politicians pandered to the consensus narrative instead of thinking critically. Now as the consequences of this flawed policy are becoming clear, governments are doing a sharp U-turn and trying to convince people that nuclear power isn’t that bad after all. Oliver Stone’s new documentary on nuclear power was even featured at the World Economic Forum at Davos recently, something that would have been unimaginable just a few years ago.

In the US, 3 plants representing 5GW that were scheduled for closure applied for and received permits to extend their operations recently. Many more reactors in the US whose futures were uncertain are now likely to remain operational given the $15 per MWh production tax credit introduced under the Inflation Reduction Act. The European Union (EU), Japan and South Korea launched green taxonomies in 2022, including nuclear energy. In Japan 9 reactors (out of 54 total) were back on by year-end 2022, another reactor is coming online in Feb and there are 3 more expected to come online in the summer. A typical 1GW reactor consumes around 0.5mm lbs of uranium per year. With aggregate global demand at roughly 180mm lbs / year, all these life extensions and restarts are starting to make a significant dent in future supply/demand balances.

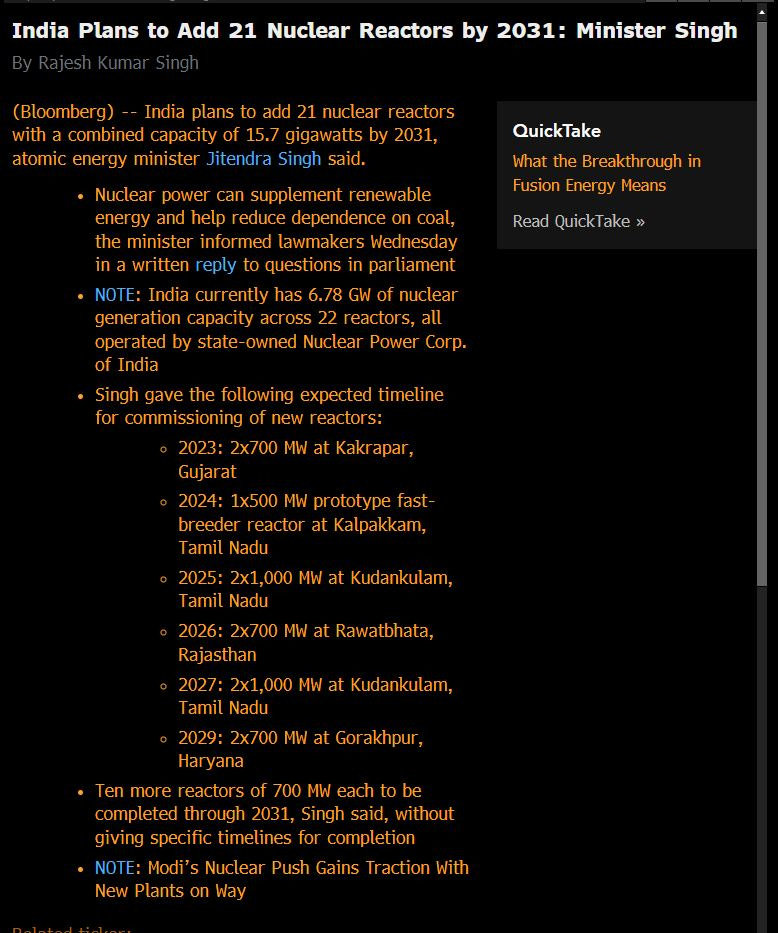

There are also a large number of new nuclear projects being announced and proposed. There are far too many to list here but just as an example, the Bulgarian parliament voted to begin negotiations with Westinghouse on a new AP1000 unit a week ago. Earlier in December, India announced a plan to add 21 nuclear reactors by 2031.

Small modular reactors (SMRs), which were considered an abstract concept just a few years ago, are fast becoming a reality and are likely to be the future driver of nuclear power growth:

The first SMR was certified for operation by the US Nuclear Regulatory Commission recently

Japan and the US have signed a deal to cooperate on SMR development

Turkey has recently been in talks with the US to purchase as many as 35 (!) SMRs.

In Europe, Poland and Romania are interested in working with US partners to develop their domestic SMR programs

Again, there are far too many proposed SMR projects to list here but the point is that SMRs are gaining traction and are a gamechanger in the industry given their smaller size (usually starting at 300MW), lower upfront capital investment, permitting timeframe and construction timeframe (not to mention operational and safety improvements). Imagine what uranium demand will look like if SMR manufacturing achieves economies of scale; it could make nuclear technology accessible to a wide range of corporate and government buyers. The first SMRs will come online by the end of this decade, but given the long cycle for uranium mining, SMR developers need to start thinking about securing fuel supplies for these reactors sooner vs. later.

All of these new conventional and SMR projects are of course on top of the 56 nuclear reactors already under construction.

In addition to all the commercial demand for uranium, there is also a major demand shock coming from ‘secondary’ sources including financial demand (physical trusts like Yellowcake, Sprott Physical Uranium Trust etc.), the switch from underfeeding to overfeeding (both of which I have discussed in prior articles and will therefore not repeat) and the DOEs recently established uranium reserve which has already started contracting pounds from domestic producers. The latter two demand factors are a direct result of Russia’s conflict with Ukraine and the West’s desire to wean itself off of Russian enriched uranium (Russia currently controls 40% of global enrichment capacity).

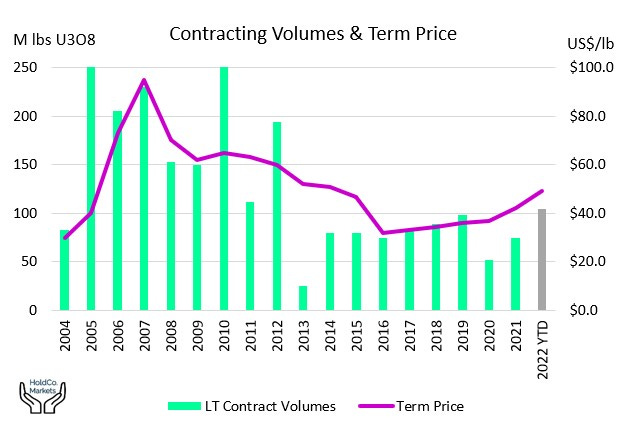

Stating the obvious, all these developments are very bullish for uranium prices. As fuel buyers and consultants revise their supply/demand math, they are coming to the realization that there may not be enough uranium available for everyone. As of year-end 2022, nuclear fuel industry consultant UxC reported that utilities have signed long-term contracts with uranium producers for 114 mm lbs of U3O8 during 2022 in 61 transactions. This is the largest annual term contract volume in a decade. For most of the past decade, utilities have only been contracting for about a third of their requirements because they were told there was ample supply available. This lack of urgency is quickly disappearing. UxC had the following to say about market dynamics a couple of months ago:

The fundamentals of uranium continue to improve, with demand for uranium now exceeding pre-Fukushima levels and global mine production expected to lag global consumption. UxC projects that the demand for the commodity will grow 21.7% to over 213mm lbs from 175mm lbs U3O8 in 2021. On the other hand, UxC is also projecting a decline in uranium supply from a potential 2028 peak of 150mm lbs to roughly 100mm lbs come 2035.

Many would argue about the accuracy of UxC’s forecast and some would calculate the deficit to be smaller or wider, but the important point here is that when it comes to nuclear market consultants, there is UxC and then everybody else. Most large utilities use UxC’s forecasts to make procurement decisions and the sharp rise in contracting last year suggests that they are listening carefully. As contracting volumes pick up, it’s going to be hard to keep uranium prices at current levels; contract pricing has been moving up steadily with some of the recent DOE contracts for the strategic uranium reserve as high as $70 / lbs.

Eventually as utilities find that all the available uranium supply has been locked up through contracts, they’re going to start dipping their toes into the spot market. The spot price for uranium conversion and enrichment has already spiked higher by 2x to 2.5x last year, reflecting these tightening dynamics. While uranium spot price was only up 13% in 2022, if you understand the nuclear fuel cycle you’ll understand why this is not going to last. With Metropolis restart, the UF6 / conversion bottleneck should start clearing up this year allowing for even more uranium purchasing to take place.

Investors are starting to wake up to this reality with SPUT +8% and the major uranium ETFs up +17-20% YTD. SPUT has finally started trading close to NAV and raised ~$40mm over the last couple of trading sessions. The trust now has roughly $55mm in cash, just enough to buy 1mm lbs of U3O8 in the spot market. The opportunity to front run and squeeze this market is enormous given how tight supplies are and how illiquid the spot market is. The last time contracting picked up in this way and investors and utilities were anticipating a supply shortage (2006-07), uranium prices tripled to $135 / lb. While history doesn’t repeat, it does rhyme and my analysis leads me to conclude that the current spot price of around $50 / lb and current uranium equity valuations continue to represent a compelling risk/reward for investors.