Understanding The Nuclear Fuel Cycle

Uranium spot prices are not accurately reflecting tightening market dynamics

“It takes longer for things to happen than you thought it would, but then they happen much faster than you thought they could.”

“In my experience, we often see positive or negative fundamental developments pile up for a good while, with no reaction on the part of security prices. But then a tipping point is reached - either fundamental or psychological - and the whole pile suddenly gets reflected in prices, sometimes to excess.”

- Howard Marks

Uranium and uranium equities have been caught up in broader markets risk-off but the fundamental bull thesis has remained intact, and in fact gotten stronger. The bullish factors for uranium are ‘piling up’. Here are some of the key developments in recent months that have made the supply / demand picture for uranium even more attractive for bulls:

EU has agreed to include nuclear in its taxonomy of sustainable sources of energy

The uranium market is becoming bi-furcated as a result of the Russia-Ukraine war which means lower ‘secondary supplies’ going forward

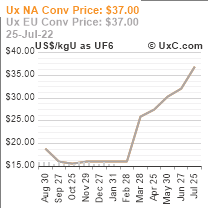

Conversion and enrichment prices are making new all-time highs

The first four points are fairly easy to understand, but in order to grasp the significance of the final two points, one has to delve a bit deeper into how the uranium fuel cycle actually works.

At a high level, the uranium fuel cycle looks something like this:

Uranium ore is mined out of the ground and sent to a milling facility where it is ground down, purified and treated with chemicals to create an intermediate product known as yellowcake. This yellowcake is what most people refer to when they’re talking about uranium or U3O8. However this product is not yet ready to go into a reactor as it’s composed ~99.3% of U238 and only 0.7% U235. U238 is the stable isotope of uranium and therefore more abundant in nature. U235 is fissile/unstable and rarer, but this instability is what allows neutrons to break it down in a fission reaction to release energy. In order for a nuclear reactor to work, it needs enriched uranium where the concentration of U235 is 3-5% vs. the 0.7% found naturally.

In order to create enriched uranium from yellow cake, the yellowcake is first converted to an intermediate gaseous product called uranium hexafluoride (UF6). This gas is then sent into a enrichment facility where centrifuges are used to slowly increase the concentration of U235. Once the desired enrichment level is reached, the enriched gas is then converted back into solid state in the form of pellets which are fed into the fuel rods at nuclear reactors. In summary the process involves mining (uranium ore) → milling (yellowcake / U308) → conversion (UF6) → enrichment.

One interesting aspect of the enrichment process is the phenomenon of under and over feeding. It’s easiest to explain this through an analogy. Suppose you have a freshly squeezed orange juice stand and business is going extremely well. You have a long line of customers waiting for your orange juice everyday and as a result you have to squeeze the oranges quickly to keep the line moving. Now supposed that for some reason demand dropped and you have far fewer customers. This means you can now squeeze oranges slower and harder, getting more juice out of them. If you needed 3 oranges for a cup of orange juice, maybe now you only need 2 or 2.5.

For a uranium enrichment facility, when global stockpiles are high and demand is low the facilities can ‘underfeed’ their centrifuges by spinning them at lower speeds. This means the enrichment process is slower, but it also means the centrifuge requires less yellowcake / U3O8 than if it was running at normal speed. This underfeeding process can exacerbate an oversupply situation creating a ‘secondary’ supply of uranium. In terms of our orange juice analogy, if there was a surplus of oranges and demand for orange juice slowed down, the fact that you can use less oranges to create the same amount of orange juice worsens the supply glut. This has been the situation in uranium for most of the last decade due to the surplus inventories created after the Fukushima incident in 2011. Underfeeding has contributed to roughly 20mm lbs of secondary supply annually over the past few years. However, the Russia-Ukraine war threatens to turn this dynamic on its head.

A separative work unit (SWU) is the standard measure of effort required to separate uranium isotopes. The chart above shows how Russia is by far the largest player in the uranium enrichment space with roughly 40% of the global enrichment / SWU capacity. After the Russian invasion of Ukraine however, the Western world is desperately trying to wean itself off of uranium enriched in Russia.

This means that Western enrichers are starting to see a large influx of demand from Western utilities looking to cut ties with Russia. In order to meet this demand Western enrichers will have to start running their centrifuges faster. As the enrichers stop underfeeding, the secondary supply into the uranium market is going to disappear. In fact if the enrichers start overfeeding the secondary supply will switch into secondary demand. If there was a complete Western ban on Russian enriched uranium, we could go from 20mm lbs / year of secondary supply to 20mm lbs / year of secondary demand, a swing of 40mm lbs / year in a market already running at a 20mm+ lbs / year deficit! A complete ban on Russian enrichment is not my base case scenario, but it’s important to keep in mind the tail risks in an already tight market.

On the Russian side, enrichment demand will slow and Russian enrichers may switch to underfeeding creating secondary supplies of uranium in Russia. This may sound like it will offset the over feeding we described earlier, but Russia will struggle to sell these pounds in the Western markets and instead likely sell to friendlier countries like China, India who have a large and growing need for uranium given their future nuclear expansion plans.

Overall, this development of a bi-furcated uranium market is bullish for Western uranium miners. As enrichers switch to overfeeding they will demand more U3O8, and in order to source the U3O8 they will have to contract with Western / friendly uranium mining jurisdictions. With the uranium mining industry suffering from years of underinvestment, higher uranium prices will be needed to incent miners to bring on more supply. I’ve written previously about how high uranium prices might go. The CFO of Cameco also made the following statement during the company’s recent earnings conference call: “An incentive price of $70/lb level is needed to bring on new mines in this bifurcated market, and we wouldn't argue with a price $20/lb higher due to inflation".

While uranium spot prices have languished, conversion and enrichment prices have been shooting to all-time highs reflecting these tightening market fundamentals. The price of UF6 was in the mid-teens at the start of this year and has increased more than two-fold to $35+ / kgU. The price of enrichment, measured in dollars per SWU, was around $55-60 at the start of this year and has increased to $90. In fact, there is almost no spot enrichment capacity left. For longer term SWU contracts the price is $130+.

These price movements indicate that utilities are currently focused on securing supplies in the conversion and enrichment market and that demand is extremely strong. If you don’t understand the nuclear fuel cycle and are focused only on the uranium spot market price, you will miss these important signals. Ultimately, strength in enrichment and conversion prices will get reflected in uranium prices as conversion facilities and enrichers will require more U3O8 to keep up with the demand.

To summarize, the uranium market is fundamentally strengthening but spot uranium prices are not yet reflecting this because yellowcake is the earliest stage of the fuel cycle. The absence of Sprott Physical Uranium Trust (SPUT) purchases has also led to liquidity drying up in the spot market. It’s only a matter of time though before the fuel cycle works its way through to yellowcake/uranium prices. If financial markets stabilize in the near-term and investors push SPUT back to a premium to NAV, the move in spot prices could happen a lot sooner.