Last year I predicted uranium prices would eventually spike to triple digits. This week, spot prices broke the $100 mark and are currently sitting at around $104. A number of folks have messaged me asking if it’s a good time to close out of uranium positions. I spent some time over the holidays thinking about where we are in the cycle, and the conclusion I reached is that the current uranium cycle is quite unlike any we have seen in history. Whether it’s the severe underinvestment the industry has suffered from over the past decade, the chronic nature of the deficit, the demand momentum, or the geopolitical bifurcation of uranium supply, the current setup is still incredibly bullish, no matter how you look at it. As such, while I have started taking profits, I’m still holding on to a majority of the investment.

In the last bull market in 2007-08, prices spiked to $138 / lb, but the market remained in surplus. The sharp increase in price at that time was driven by the Cigar Lake flood, and a perception of oncoming shortages, which never materialized. There were also various supply buffers available. For example, the megatons to megawatts project (an agreement between Russia and US to convert excess weapons-grade uranium into low enriched uranium for use in US nuclear power plants) provided 9-10mm lbs of annual uranium supply up to 2013, the DOE sold its strategic uranium reserve to alleviate price pressures, and enrichers sold excess UF6 generated through underfeeding. The demand picture was also not nearly as robust.

Today, the entire nuclear fuel supply chain is stretched and operating at the limits. Prices are gapping higher across enrichment, conversion, and spot uranium. Demand pressures are climbing relentlessly; reactor restarts, extensions and flex-up provisions are leaving producers scrambling for pounds, forcing the largest miners like Cameco to source pounds from the spot market to meet contractual obligations. New projects, both conventional and SMR, are being announced almost daily. Not only are there no supply buffers left in the form of excess inventories or secondary supplies, there are in fact increasing secondary demand pressures as enrichers switch to overfeeding, and financial players look to benefit from rising prices. Western utilities are also realizing they can no longer rely on uranium fuel coming from the East.

The reality is that a spike in uranium prices won't cure the supply deficit. Uranium prices could spike to $300 / lb tomorrow, and it won’t change the primary supply situation in the near term (though it may shake loose some pounds held by financial players or producers looking to monetize their stockpiles to fund capex). Uranium mining is hard. It’s arguably the most regulated commodity in the world, and the most difficult to get acceptance with locals. Very few mines ever go into production and it typically takes 10-15 years to bring new projects online. This makes short to medium-term supply inelastic. This is unlike a commodity like oil, where if prices spiked to $150 / bbl, you would see a significant supply response from all corners of the globe within 12-18 months.

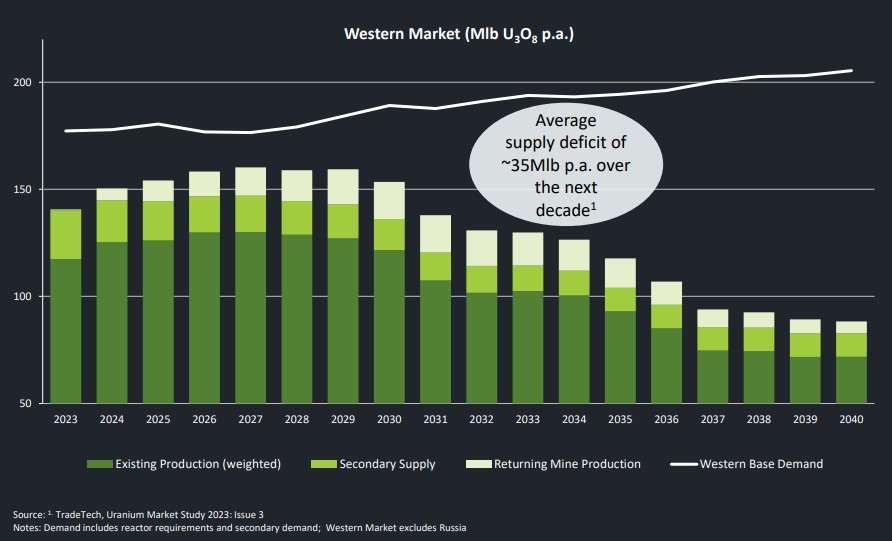

I’ve seen some folks compare the uranium price action to crypto or high growth tech stocks, but such comparisons are misplaced. The uranium bull market is ultimately underpinned not by speculative fervor or hyper optimistic assumptions about the future, but rather simple math. 2024 uranium consumption is expected to be 175mm lbs, supply is 145mm lbs. Importantly, the 175mm figure does not represent total demand. Uranium demand is much higher than the annual consumption of operating reactors because it also includes strategic stockpiling by countries like China, utilities re-stocking, enrichers demanding extra U3O8 for overfeeding and financial demand.

Let’s take a look at potential re-stocking demand for Western utilities. Currently 71% of nuclear generation is coming from the West. If Western utilities decide they want to re-stock their inventories and add 3 months more of inventory, that’s 71% x 25% x 175mm = 31mm of additional buying. 6 months = 62mm, 9 months = 93mm etc. This means the supply deficit is not 30mm, but could be as high as 60-100mm. Why would utilities want to re-stock now? Because since the Fukushima accident, utilities have been buying significantly less uranium than their annual needs, and drawing down stockpiles. Why did they do this? Because they were told that the world is swimming in cheap uranium, that demand was unlikely to increase and that they could always buy more in the spot market.

This assumption has turned out to be false and the situation has turned 180 degrees. After years of deficits, excess stockpiles have vanished. A lot of the excess inventory sitting in Japan is no longer available as the country has decided to restart its nuclear facilities. A number of nuclear reactors slated for closure have had their lives extended and are in the search for pounds. Financial players like SPUT and Yellowcake have further cleaned up any excess available spot pounds. On top of all this, there is supply insecurity for utilities that have contracted with Kazatomprom and other Russian-influenced suppliers. Fuel buyers are now adhering to the adage, “if you must panic, panic early”. This is why uranium spot prices have been gapping up relentlessly.

Is there any supply relief on the horizon for 2024/25?

What about stockpiles?

China is sitting on 500mm+ lbs of inventory, but these pounds are highly strategic given the intensity of China’s nuclear buildout, and the fact that China produces very little uranium of its own.

A couple of producers have stockpiles. Denison owns 2.0mm lbs, Uranium Royalty Corp. (UROY) owns 1.5mm bls. These will eventually be sold, but the timing is not clear, and they won’t make a dent in the deficit.

SPUT owns 63mm lbs and Yellowcake owns 20mm lbs, but these have been sequestered for the purposes of financial investment.

Can the large producers Cameco, Kazatomprom provide any relief? The answer is: no. Future production is fully booked out to 2026 - 27.

As of September 30, 2023, Cameco has commitments to deliver 29mm lbs / yr from 2023 - 2027. 2024 production forecast: 22.4mm lbs. Cameco is, and will continue to be, a buyer of uranium in the spot market to fulfill its commitment obligations.

I’ve already written at length about Kazatomprom’s situation, most recently here. In short, the company has serially underperformed production targets and has overcommitted production, similar to Cameco. This Friday, KAP warned that it was unlikely to meet its production targets for the next 2 years. If you’ve been reading this blog, this shouldn’t come as a surprise. But market participants seem to have been unprepared, leading to a sharp rally across uranium stocks.

What about emerging producers / mines?

Paladin? The answer is again: no. The company will be producing 6mm lbs / yr starting 2024, but there is only 100K lbs or so left to be sold. The rest is already contracted.

Budenovskoye 6&7 - 6.5mm lbs / yr starting 2024, already fully contracted to Russia.

Boss Energy and Lotus - could each produce 2.4mm lbs / yr by 2025. Boss is looking for LT contracts to sign.

Energy Fuels (UUUU) - can produce 1mm lbs / yr by 2025.

UR Energy (URG) - can produce 1.2mm lbs / yr by 2025.

EnCore Energy (EU) - can produce 1.3mm lbs / yr by 2025.

Peninsula Energy (PEN) - can produce 1mm lbs / yr by 2025, but already fully contracted.

Uranium Energy Corp (UEC) - can produce 1mm lbs / yr by 2025.

There are probably a couple of smaller projects that I’m missing here, but you get the picture: even if the large producers met their production targets, and all the emerging producers come online as expected, without delays (which is a rarity in the mining business), the increase in supply over 2024 / 25 is miniscule compared to a potential 30mm lb deficit, which could balloon to 100mm+ if utilities start restocking in earnest.

I haven’t discussed the Tier 1 / ‘big hitters’ yet - Global Atomic (GLO), NexGen (NXE), Denison (DNN). I own all three stocks as they are pivotal to bringing some semblance of balance to the market in the latter half of this decade:

GLO can produce 4.5mm lbs / yr from its Dasa mine, but production is likely pushed out to 2026 after the recent events in Niger.

Denison Mines Phoenix Project can produce 9mm lbs / yr, but it won’t start producing until 2027-28.

NexGen is the elephant in the room, with the potential for 29mm lbs / yr. But Arrow’s size and complexity will require extensive preparation and it’s not expected to produce until 2030.

Fission Uranium can produce 9mm lbs / yr, but it won’t start producing until 2030.

Denison Mines Gryphon Project could bring another 9mm lbs / yr online starting 2034.

The problem is that by the time Tier 1 developers are in production, demand will have risen even more and the largest producers like Cameco and Kazatomprom will have depleted a lot of their core inventory. Therefore, I can see the potential for the uranium thesis to continue for multiple years beyond the near-term supply shortfalls.

Below is a nice graphic putting together the major uranium development projects and their timelines:

Coming back to the original question: is it time to sell uranium? Based on my view of the sector and the supply / demand math laid out above, I think it’s too early to sell. So how does one go about timing the exit? I have come up with the following list of data points / markers:

Last cycle’s price peak of $138 / lb equates to $200 / lb today, in inflation-adjusted terms

At $200 / lb price, uranium extraction from phospate, copper, gold tails becomes profitable

At $500 / lb price, uranium extraction from sea water could become viable

Overall, there is plenty of uranium in the earth’s crust. It’s just a matter of price incentive, and the time required to extract it.

The entire uranium sector, which fuels 10% of the world’s power generation, has a market cap of around $60bn.

To put this in context, this is 15% of the Exxon Mobil’s market cap, or 9% of Tesla’s market cap.

At the peak of the last cycle, the total uranium sector market cap was $150bn.

Unlike the last cycle, there is an actual structural deficit and strong demand momentum.

Inflows into ETFs and physical trusts could lead to a flywheel effect: ETF buying leads to higher stock prices and increased liquidity, which attracts more investors, including institutions, leading to even more buying.

I think a $500bn+ valuation for the uranium sector is not inconceivable.

The fuel cycle and pricing curve structure will provide important clues regarding how tight the market is.

Just as oil investors look at crack spreads to judge the strength of end-user demand, uranium investors should look at enrichment / SWU and UF6 prices.

A drop in SWU prices would indicate that the market for the end product (enriched uranium) is starting to loosen up.

Currently the uranium market is in steep backwardation due to the acute shortage of pounds. When LT prices rise above spot prices, that will be an indication that utilities have contracted enough uranium to satisfy their needs, alleviating pressure from the spot market, and marking an end to the shortage phase.

When mining equities start trading at a premium to their NPVs, it’s usually a good time to book profits.

If you own a uranium mining equity, you should have a sense for its NPV at various uranium prices and discount rates. This will allow you to assess the relative upside and margin of safety present at the current valuation.

For my uranium investments, I will start scaling out of positions once they reach their NPV at $80 / $100 / $150 uranium price at a 10-12% discount rate.

As the cycle matures, M&A will heat up in the sector. I can foresee large oil and gas companies and mining giants acquiring uranium companies to their portfolio, especially as the uranium developers de-risk their assets and get closer to production. An increase in M&A activity will be a sign that the cycle has started to mature.

On a short-term basis, when a stock’s daily RSI climbs >80, when it approaches an important resistance and/or trading volume starts to dry up, that’s usually a sign that the near-term uptrend is over, and a down-trend might be starting soon. It’s important to learn how to read stock price charts to optimize your entry and exits. Please read my piece on technical analysis and momentum here.

Finally, you should take profits based on your personal financial situation and risk tolerance. Everyone has to evaluate their position sizing, risk management and exit strategy based on their own circumstances. Uranium is a volatile sector, and if you think you’ve made sufficient profits, and that you will need the liquidity in the next 6-12 months, you should de-risk your positions. As the saying goes, no one went broke taking profits.