Note: this is the first writeup in a multi-part series on the copper investment thesis. I’m hoping to cover copper demand here, and write separate notes on supply, stock selection as well as risks to the thesis. I’ve been accumulating shares in a handful of copper miners over the past couple of months (tickers: ERO, ARG, FOM, ALDE), however these remain starter / low conviction positions as I continue to research the thesis. My aggregate exposure to the sector is still <10% of my portfolio NAV.

“There is a huge crisis. There’s no way we can supply the amount of copper in the next 10 years to drive the energy transition and carbon zero. It’s not going to happen. There’s just not enough copper deposits being found or developed.” - Doug Kirwin (geologist)

The copper market has frustrated bulls over the last couple of years. In 2022, China’s property sector woes, second COVID wave, and the threat of a global recession caused a sharp 38% drawdown in prices from a peak of ~$5.05 / lb in March to ~$3.13 / lb in July. Copper investors then enjoyed a relief bounce going into the new year, but after reaching a local peak in January 2023, prices started another excruciating grind lower from ~$4.4 / lb to ~$3.5 / lb in October, as Chinese imports weakened in response to de-stocking (a function of the higher interest rate environment) and a surge in domestic refined output.

Since October last year, prices have been choppy, but are starting to regain a healthy uptrend. Inventories are now running low, and the shutting down of First Quantum’s Cobre Panama mine last year will tighten the market significantly over the course of this year. In March, China’s top copper smelters agreed to a historic production cut, citing a shortage of raw material and declining TC / IC (treatment and refining) charges. Q1 is a seasonally weak / build period for the copper market; I expect prices to move up more strongly as deficits appear from Q2 onwards. From a technical point of view, copper seems to be breaking out of a consolidation triangle pattern, which can often lead to a slingshot move higher.

There are 3 major fundamental tenets to the longer-term (2 to 3+ year) copper bull thesis:

The green energy transition and EM electrification will lead to a sharp increase in copper demand.

Electric vehicles (EVs) require 5x as much copper as ICEs.

Wind and solar power generation require 2.5x as much copper per MW as thermal generation.

Electrification is accelerating in places like rural India and Sub-Saharan Africa.

After declining for the last couple of years, DM demand is turning a corner.

The CHIPS and IRA acts are stimulating ‘old economy’ manufacturing and construction demand in the US.

Europe is coming out of a manufacturing recession.

While the Russia-Ukraine war is still far from being resolved, there will eventually be a strong copper demand pull from Europe to rebuild Ukraine’s infrastructure.

With geopolitical tensions rising, and the trend of deglobalization well underway, DM onshoring is likely to continue for many years, leading to a demand pull on all essential commodities.

Copper supply is facing severe underinvestment, with none of the major mining companies investing in growth capex.

Copper mines currently in operation are nearing peak production due to declining ore grades and reserves exhaustion.

For example, the world’s largest copper mine, Escondida in Chile, has already reached its peak; 2025 production is expected to be 5% lower than it is today.

Chile’s Codelco, the world’s biggest copper supplier, is struggling to return production to pre-pandemic levels of about 1.7 Mt/y from around 1.3Mt this year.

Similar to uranium, copper is a long-cycle commodity. It takes 2-3 years to extend the life of existing mines, and 8 years to develop greenfield projects.

Current copper price levels are not high enough to incentivize enough greenfield projects to cover the incoming supply-demand gap.

Before I move forward, it’s important to clarify my views on electrification and the green transition. I’ve written favorably about the prospects of oil, gas and nuclear, and I’ve discredited the hype surrounding EVs and renewables. This might lead readers to view my positive stance on copper as contradictory. However, this would be an incorrect inference, as I’ve never implied that EVs and renewables are not part of the solution to our energy problem. What I have criticized, is the pace at which politicians, green activists and ESG proponents think these technologies can replace traditional fossil fuels, as well as a reluctance to consider their drawbacks / shortcomings.

I’m in favor of renewable energy, as long as it’s deployed with geography in mind, and paired with adequate baseload generation from nuclear and natural gas. Solar, for example, makes a lot of sense in places like the Middle East, or large deserts, where sunlight and land is abundant. Offshore wind farms can be a good complement to baseload power in coastal communities. But blindly deploying renewables, without considering their intermittency, at the expense of baseload power, is a recipe for grid instability and power outages.

It’s pretty clear to me that we will need to rely on a mix of different forms of power generation to meet the world’s growing energy needs, and that viewing things in binary terms is detrimental to progress. Demonizing oil and gas won’t make their influence disappear overnight. It will only make investing in oil and gas more costly, leading to higher energy prices for everyone. It’s important to remember that despite all the major technological advancements of the past few decades, we haven’t even made a dent in the consumption of coal, the dirtiest of the fossil fuels. Folks who think we can somehow end our reliance on fossil fuels in a few years, or even a decade, don’t understand economics and physics.

I’m also in favor of EVs as a means to reduce emissions, as long as we keep in mind what that means for power generation. Charging EVs on a grid that’s 60-70%+ powered by fossil fuels, as is the case in the US, China, India, and most of the world, makes no sense for obvious reasons. Charging EVs on a grid that’s heavily reliant on renewables doesn’t make sense either (as the recent experience in California has illustrated clearly). In order to meet the higher electricity demands for the transition to EVs, we need to invest aggressively in more nuclear power (and some natural gas), as well modernizing the power grid and expanding charging infrastructure. This will be very copper intensive. Transitioning to EVs also requires investment in supply chains and processes to mine / extract the critical raw materials required in their manufacture in a sustainable manner.

Instead of thinking through these issues in a holistic manner, governments seem to be content throwing money on the EV and renewables markets in the form of subsidies. I believe that subsidies are distorting market signals, generating ‘artificial’ demand, and reducing the incentive for renewables and EV manufacturers to invest in the innovation and quality improvements necessary to move these technologies forward. They are also taking funding away from other critical green technologies such as advanced nuclear, carbon capture and improving ICE efficiency.

With that long preamble out of the way, let’s turn to copper demand fundamentals.

Copper’s Demand Story

Copper demand can be broken down broadly into two categories: green and non-green. Green demand can be further broken down into EVs, renewables (solar, wind and associated transmission grid), energy storage and charging infrastructure. Non-green demand can be broken down into buildings and infrastructure, transport (ICEs require copper too), non-green power network / grid, industrial machinery and electrical appliances.

In 2022, total global copper demand was ~30.9Mt (including scrap use), of which only ~2.1Mt or 7% was related to decarbonization (i.e. ‘green demand’). Almost half of 2022 green demand came from China (0.96Mt), with the EU a distant second (~0.5Mt). From a category perspective, solar accounted for 38%, EVs 33% and wind 27% of green copper demand, with the rest (2%) coming from energy storage and charging infrastructure.

In 2023, total global copper demand is estimated to have grown by 2.5% / ~0.76Mt to ~31.7Mt, with ~0.52Mt / 70% of the growth coming from green sources. On a country level, copper demand for solar installations in China had the biggest impact, growing 138% YoY (from 0.28Mt to 0.68Mt) and contributing to almost half the increase in global green copper demand. EV copper demand also contributed strongly, increasing by 47% in the US, 30% in China, 17% in the EU and 252% in the RoW. Total EV copper demand increased 34% from 0.67Mt to 0.90Mt. On an aggregate basis, Chinese green demand continued to dominate, representing 56% of global green demand.

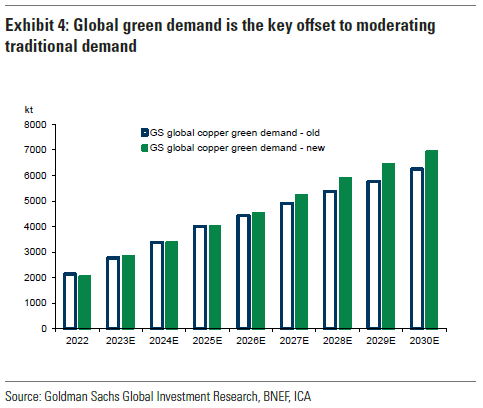

Looking forward, the trends in green copper demand are expected to accelerate. Most analyst and consultant demand models that I’ve studied expect 2030 total copper demand to be in the 36 - 38Mt range (including scrap usage), driven by a ~2 - 2.5x increase in green demand from around 2.9Mt in 2023 to 6-7Mt by the end of the decade, implying a CAGR of 11-13%. Decarbonization demand’s share of total copper demand is expected to increase from 7% to ~20%. Non-green demand is expected to grow modestly from ~29Mt in 2023 to ~32Mt by 2030, implying a 1.4% CAGR.

These forecasts follow commitments made at COP28 by global powers to target tripling of renewable capacity by 2030. In 2020, China committed to becoming carbon neutral by 2060 and having 1,200 GW of renewable capacity by 2030. But it’s on track to meet that commitment almost 5 years early, focusing developments on desert regions like Gobi where solar resources are abundant. China could have as much as 1,000 GW of solar power alone by 2026, and it is expected that 11,000 GW will be needed globally to meet the Paris Agreement targets by 2030.

This year, Chinese copper demand growth for solar is expected to decelerate sharply from 138% / 0.4Mt to 4% / 0.03Mt. China accelerated / pulled forward its solar installations in 2023 to boost the economy. However, offshore wind projects are budgeted to accelerate, and grow by 19% / 0.07Mt. The PBOC also plans to provide RMB 1 trillion liquidity for social housing construction this year, which should boost non-green building / infrastructure demand. Overall, Chinese demand is expected to increase by 0.4Mt / 2.5%, a slowdown from last year’s ~7% growth.

In contrast, the outlook for ex-China EM and DM demand this year is looking brighter vs. last year. Global manufacturing PMIs are healthy after a year of contraction, and economic growth is robust in other EMs (India, Africa etc.). Ex-China EM copper growth is expected to outperform and grow ~3.7% / 0.18Mt, vs. slight -0.5% decline last year. DM growth is expected to pick up from a -3% decline last year, to a +1.5% / 0.15Mt increase this year, driven by a rebound in European manufacturing, re-stocking, and CHIPs / IRA spending. Putting all this math together, copper demand is expected to increase by 0.6-0.7Mt this year.

Another potential demand stimulant this year is the start of a monetary easing cycle. If inflation continues to moderate (though there is a risk of a second inflation wave, as I have written about here), and central banks start cutting rates, that would provide an additional boost to both physical and financial demand for copper.

Historically, interest rate easing cycles have led to strong rebounds in manufacturing, and increased financial positioning in industrial metals. Copper tends to show the strongest performance when the global manufacturing cycle rebounds.

Lastly, we have to think about how the financial demand for copper behaves in relation to physical demand, and how this compares to other commodities. Copper is the only liquid commodity in the major futures indices that has a direct linkage to decarbonization. Daily trading volumes are around $30bn, which is ~7x nickel, ~6000 times cobalt and ~15,000+ times lithium futures. This means that copper futures and copper ETFs should benefit disproportionately from ESG-related investing flows.

Despite the higher futures market liquidity vs. other green metals, the copper market is still relatively small in comparison to other major commodities. Annual copper consumption is less than a 10th of annual oil consumption in dollar terms. This means that even moderate amounts of futures buying and selling can have an outsized impact on copper prices. It takes only ~$2bn in copper futures buying to offset a physical surplus of 1%, vs. $27bn for oil. Historically, the volatility in copper spec positioning as a percentage of market size can be 10x more than for oil, which effectively means futures positioning often sets prices. For example, in Q2 - Q3 2020, despite a physical surplus of 0.5Mt, prices went up from ~$3 to $4 / lb due to 1.5Mt of financial buying.

Financial buying is likely to increase significantly as investors look to add exposure to the decarbonization trade, as well as exposure to global manufacturing / growth rebound, especially if we enter a rate cutting cycle globally. Citi has laid out a hypothetical scenario below where index funds increase their allocation to copper from 5% to 15% in light of decarbonization trends, and hedge funds add $10bn of net length. This would equate to speculative positioning increase of 4Mt, which would be double the prior highs in positioning. Such financial demand alone could push prices 50%-60% higher.

Conclusion

As the world transitions towards green energy, a number of technologies, including nuclear, renewables and EVs will see a significant increase in demand.

Copper is essential in this transition, given its intense usage in electrification, renewables and EV manufacturing.

Chinese green demand grew 27% in 2022, 67% in 2023 and is expected to grow 10% annually until 2030, representing a ~2x increase from 2023 levels.

In the US, the IRA will stimulate demand for renewable energy, EVs, grid storage and charging infrastructure, all of which require more copper.

Globally, green copper demand is likely to increase by 3-4Mt by the end of this decade, representing 12-16% of global refined copper production.

Outside of the green transition, traditional copper demand is also expected to rebound, as the global manufacturing cycle appears to have troughed.

In emerging economies like India and Sub-Saharan Africa, demand is expected to grow for many years as governments connect the poorer segments of their population to the grid for the first time.

The AI revolution could be an additional source of demand, as data centers and semiconductor manufacturing all require copper.

Total non-green demand is expected to grow by 2-3Mt by 2030. This means the total call on copper supply (green + non-green) will be 5-7Mt over the next 7 years, or 20-30% of current refined production.

For investors, copper is the most liquid metals play for exposure to the decarbonization trade. However, trading volumes are tiny when compared to major commodities like oil. Demand for green exposure, combined with macro traders wanting to play a manufacturing rebound, could lead to an outsized move in copper prices.

In the next piece, I will cover whether copper miners can meet these increased demand pressures.

Thanks.