Predicting The Future

Investing requires thinking in a probabilistic framework, not having a crystal ball

It’s that time of the year again when Wall St. analysts, hedge funds, economists etc. all publish their predictions / outlook for the next 12 moths. Some are predicting runaway inflation and a market crash, others a market melt-up. Some will publish very specific numerical forecasts for macro indictors like interest rates, gold, currencies etc. While others will take a more qualitative approach and discuss key ‘themes’ for the year ahead. Most of these predictions / ‘analysis’ will be wrong, yet everyone insists on engaging in this exercise year after year.

One reason is that there is a misconception about what successful investing means. When I tell people I work in finance or that I’m an investor, they often start asking me for specific predictions, like the outcome of an election or where the S&P500 might be next month. But the future by definition is unknowable, so this is a futile exercise. How many people successfully predicted and traded stocks based on Donald Trump being elected President? What about the US-China trade war? Or the COVID-19 pandemic? How many correctly predicted that the S&P500 would return >100% over the last 5 years?

I’m sure there are some exceptions, but for the most part these events were very difficult if not impossible to predict. This doesn’t mean however that we can’t make any predictions at all. A physicist for example can make very accurate predictions about physical systems, such as the motion of a pendulum or the orbits of planets. This is because these systems follow strict, inviolable rules. But finance and economics are a completely different game. It’s impossible to build a completely accurate mathematical model for human behavior, and it’s the aggregate of human interactions that form the economy and the marketplace.

This is the essence of ‘risk’: in the realm of society, politics, the economy and the markets (or any other system driven by human decision making), more things CAN happen than WILL happen. If this wasn’t the case, all financial assets would be ‘risk free’ and investing would be pretty boring indeed.

(Side note: this is where the quants got into trouble during the 2007/08 financial crisis. They believed their mathematical models for the housing market and mortgage defaults were so accurate that they could create very low risk instruments like the ‘AAA’ rated CDO tranches. They assumed (incorrectly) that housing prices, which are inevitably driven by complex human behavior, would never go down.)

The job of an investor is not to make specific predictions about the future, but rather to apply a probabilistic framework around the various possible outcomes, and then allocate capital in a way that benefits from this distribution of outcomes.

For example my investment in energy stocks is not predicated on a specific oil price forecast, or a specific outcome of the stock market and economy. Rather I have a probabilistic framework that suggests that it is very likely that 1/ oil demand will continue to grow in 2022 as the pandemic recedes and 2/ oil supply growth will continue to be weak as a result of historical underinvestment in capex. As a result I believe there is a high probability (but not certainty) that oil prices will continue to appreciate in the new year ($70 - $80+, if I had to put a range on it) and that my oil investments will flourish relative to their valuations today.

Notice that I use words like ‘likely’ and ‘high probability’ to acknowledge the risk inherent in this investment. There is also a likelihood (say 30%) that the stock market crashes, the US economy enters into a recession and oil demand takes a hit, pushing oil prices below $50 / bbl. Does that mean that I shouldn’t enter into this investment?

Let’s apply a probabilistic framework to evaluate. I know that oil stocks are deeply undervalued relative to my oil price outlook and that I could double my investment next year if the bullish oil scenario plays out. However, my oil investment is also leveraged and the company I invested in will go bankrupt if the recessionary scenario played out. Suppose the stock is trading at $1 right now. So the two outcomes are that the stock can either double to $2, or go to zero. The expected value of this investment is $0.4 ((70% x $1)+(30% x -$1)). The positive expected value suggests I should take this bet. But I’m still worried about losing all my capital. After all a 30% chance means I lose all my money roughly one out of every three times.

This is where the concept of margin of safety comes in. Because the future is unknowable, and because permanent loss of capital is the worst thing that can happen to you as an investor, the best investors will look for opportunities where their downside is limited even when the worst case scenario happens; the classic heads I win, tails I don’t lose much.

Imagine I find a different oil company, one that has a clean balance sheet and excellent management team. Because of its lower leverage, this company doesn’t have the same upside potential but can still return a healthy +70% in my bull case scenario. However, more importantly, because of the strong balance sheet and management’s capital allocation abilities I only see 20% downside during a market crash scenario. Notice that despite the lower upside, the expected value of this bet is HIGHER (0.43). Also notice that in this scenario I conserve 80% of my capital in the worst case scenario, allowing me to move on from the loss and live to fight another day.

A 70% chance of a good outcome in an investment is extremely rare. In many scenarios you’ll be looking at 60% or even 55% chance of things working in your favor. Sometimes you won’t have access to good information, or your analysis will be missing some key elements. This means your probability estimates might be incorrect. All of this means you need a bigger margin of safety to make the investment worth it. The greatest investors have a knack for finding the rare opportunities where the odds are stacked in their favor, downside is limited AND where they have the necessary skill set / circle of competence to accurately assess those probabilities, giving them the the confidence to invest in size.

One of my favorite investment quotes from Charlie Munger highlights this same point more eloquently: “It's not given to human beings to have such talent that they can just know everything about everything all the time. But it is given to human beings who work hard at it – who look and sift the world for a mispriced bet – that they can occasionally find one.” Charlie seems to be saying that it’s impossible to know the future exactly because there are too many variables involved and you would need to know ‘everything about everything’ to have a true crystal ball. However, if you work hard enough, you can sometimes find investment opportunities that don’t require perfect information because of the asymmetric odds and large margin of safety.

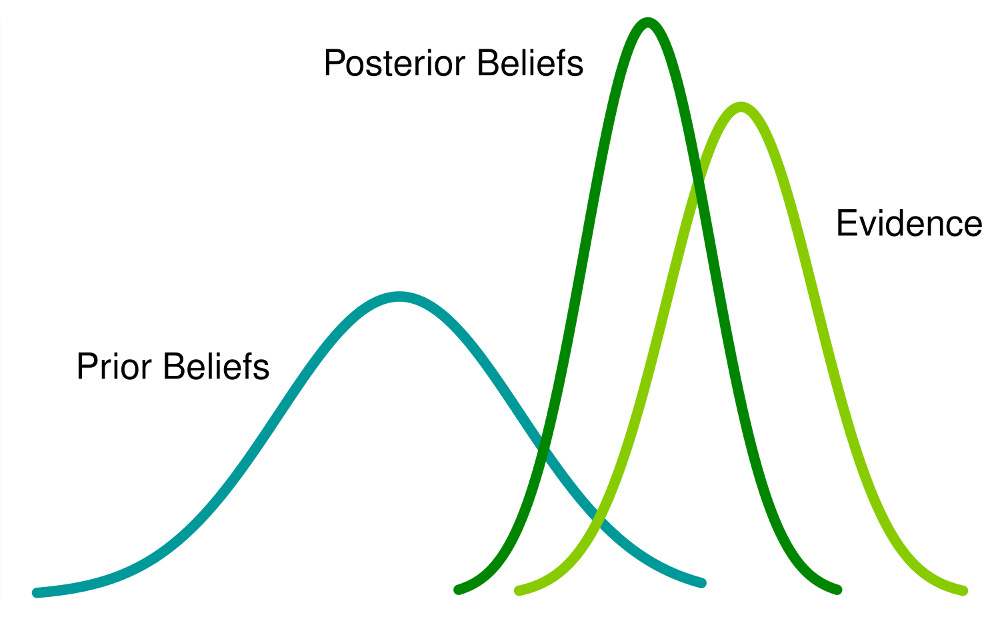

Also keep in mind that when I used the word ‘probability’, I’m not talking about it in a strict computational sense. Investing is not about spending inordinate amounts of time trying to compute exact probability figures for certain outcomes. Such a calculation is impossible. Instead, what I’m trying to convey is that as an investor you are constantly reading, learning, analyzing information to get a better sense of the ‘rough’ odds in favor of your investment and quantifying (again, approximately) the upside and downside potential under various scenarios. As you gather more information, you constantly update these rough estimates to ensure your investment decision is still a good one. This is also knows as Bayesian inference / Bayesian updating.

Ultimately your investment decision boils down to judgement, and the confidence you have developed by learning about the specific company / investment in question.

What makes investing special and particularly enjoyable in my mind is that it can never be a strictly scientific nor a completely subjective exercise. It involves effort from both sides of your brain: you need to have the creativity and imagination to visualize what the future may look like, as well the numerical competency to quantify the odds and financial outcomes related to those future states.

The next time someone offers you investment advice based on specific predictions about the future, take it with a grain of salt. The folks who know what they’re doing will speak in terms of probabilities and margin of safety, not certainty.