Downside Protection, Quick Thoughts On Waller's Speech, And A Follow Up On Inflation

With my largest position (uranium) off to a good start this year, I’ve been thinking about macro risks and have added some downside protection:

SPX December ‘24 options combo: sell 5000 / 5200 call spread to fund 4500 / 4000 put spread (net credit)

SPX March ‘24 4600 / 4000 put spread

IWM March ‘24 185/175 put spread

VIX March ‘24 20 / 25 call spread

In my 2024 macro outlook, I had expressed concern that the market had started front-running the disinflation narrative too aggressively, and that the Fed’s dovish pivot might prove to be premature. On Tuesday this week, Fed governor Chris Waller gave a speech at the Brookings Institute in which he tried to cool market expectations and reset the narrative. While acknowledging that good progress has been made on achieving the inflation target, Waller cautioned that there was no need to cut rates “as quickly or as aggressively” as past cycles because the labor market and economy remained solid. He also poured cold water on the idea that inflation was mostly a transitory / supply-driven phenomenon:

“Well, just from a simple macroeconomics point of view, if you’re going to increase the spending by $6 trillion in a matter of tow years, and then say that has no effect on demand - that seems just impossible to me…

… if these are temporary supply shocks, when they unwind, the price level should go back down to where it was. It’s not. Go to Fred. Pull up CPI. Take the log. Look at that thing. The [price level] is permanently higher.”

I’ve seen some market participants downplay the speech, but I think these comments should make investors ponder the distinction between the need for cuts, and the timing and quantum of the cuts. My takeaway is that the Fed is not signaling easy monetary policy, but rather trying to maintain the current level of restrictiveness in light of the decline in inflation. If the Fed didn’t do anything and inflation kept dropping, this would increase real interest rates and make policy more restrictive, which is not needed at this point. My other key takeaway is that the Fed is acutely aware of the impact fiscal spending is having on aggregate demand and inflation, and that this is making the Fed’s job much harder.

One of the reasons the markets have been so aggressive in pricing in rate cuts is recency bias. In the major easing cycles over the past couple of decades, the Fed has always ended up cutting aggressively as it has been behind the curve and taken too long to act. In 2001, when the dot com bubble burst, the Fed cut rates from 6% to 1.75% within 12 months. During the GFC, rates were cut from 4.75% to 0% in just 15 months, between September 2007 and December 2008. Many market participants are wondering whether the current cycle will rhyme with the recent past. Maybe the Fed is now worried that it has overtightened? Maybe there is something in the economic data that has scared the Fed? Or maybe there is something nefarious going on in the banking / credit markets that the Fed has visibility to, but we don’t?

I think Waller’s recent comments are a strong indication that these modes of thinking are incorrect. This cycle is different, and the Fed is telling us that the messaging around cuts is simply an acknowledgment that inflation has come down, and that rates also need to come down to maintain the current level of restrictiveness. I also think the Fed wanted to get this messaging out as soon as possible due to the elections. If the Fed decided to wait for more inflation data, and was then forced to make a dovish pivot a few months before the elections, that would put it in an awkward spot.

What does all of this mean for investors and traders? I think it means that one shouldn’t expect interest rates to be cut aggressively unless: 1/ the economy weakens significantly and/or 2/ inflation continues coming down rapidly. Which in turn means that the markets remain fragile. In response to Waller’s speech, the front-end of the bond curve had one of its worst weeks in recent memory and the 10Y bond has given up more than half its gains since the December 13th ‘pivot’. The Russell 2000 has fallen ~6% from its late December high. The SPX and QQQ have bucked the trend, but positioning is starting to look stretched, especially in light of the strong performance over 2023. Tech equity funds saw their biggest two-week inflow since August at $4 billion, as per BofA data. A bearish macro catalyst could have an outsized impact on the downside.

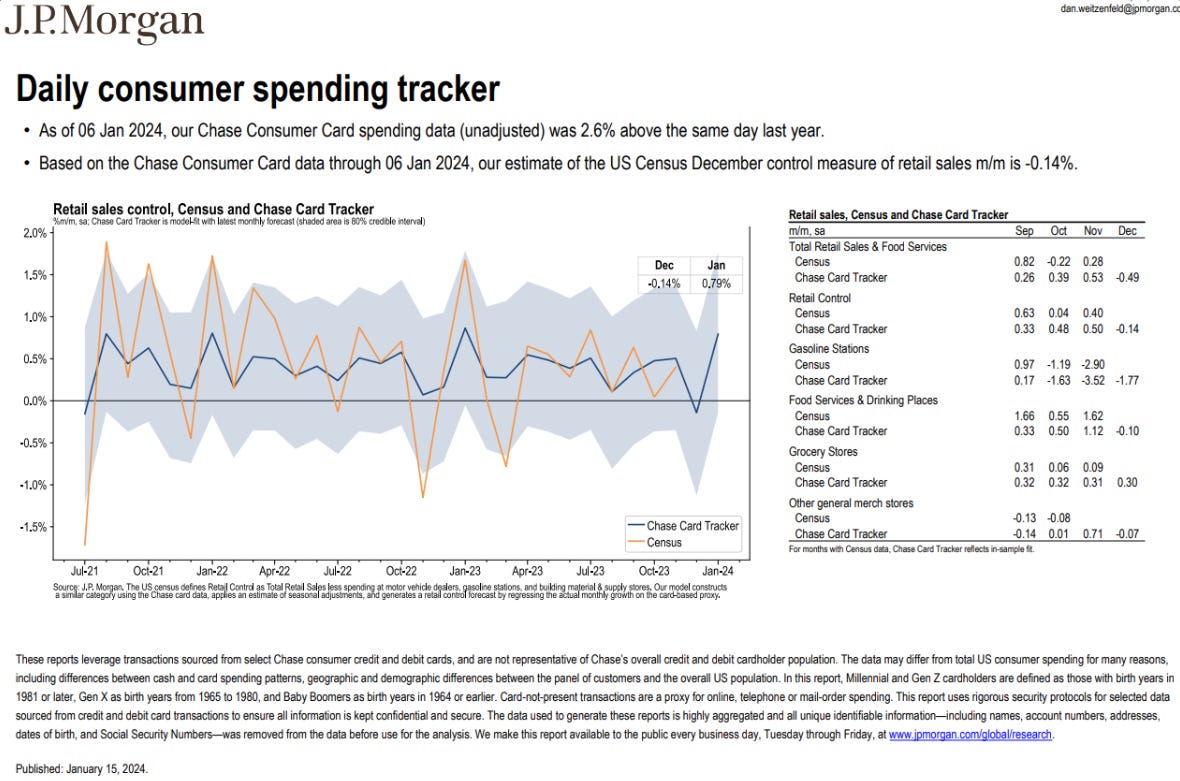

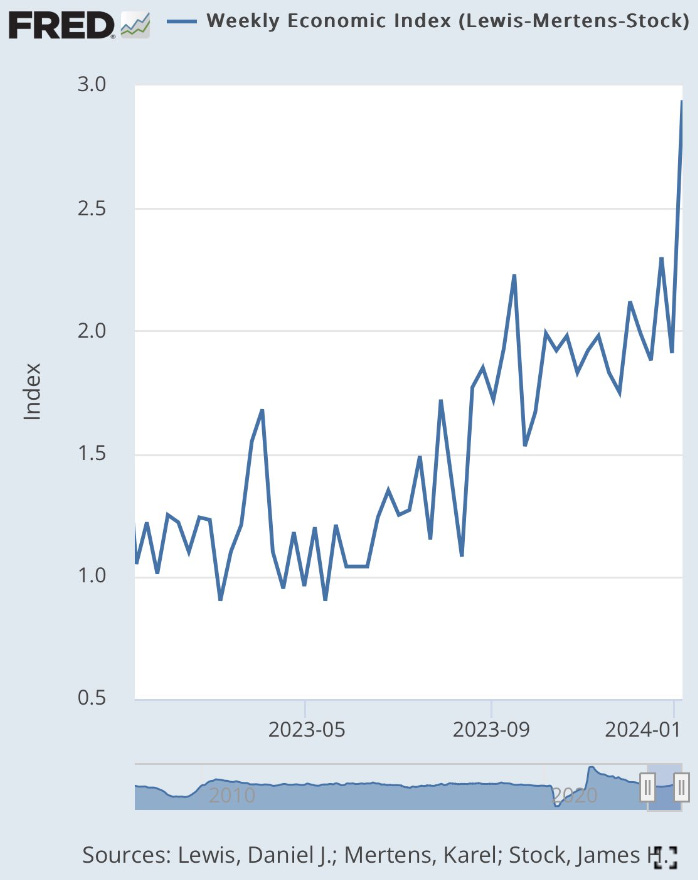

Looking at the latest economic data, there is little evidence that the economy is weak. It’s now clear that Q4 will be another strong quarter with GDPNow estimate firming up from 2.2% to 2.4% after this week’s strong retail sales print. High frequency data like JP Morgan’s Daily Consumer Tracker and the NY Fed’s Weekly Economic Index (WEI) are showing a strong bounce in spending and economic activity in January. The Michigan Consumer Sentiment Index rose to 78.8 on Friday, vs. expectations of 70.

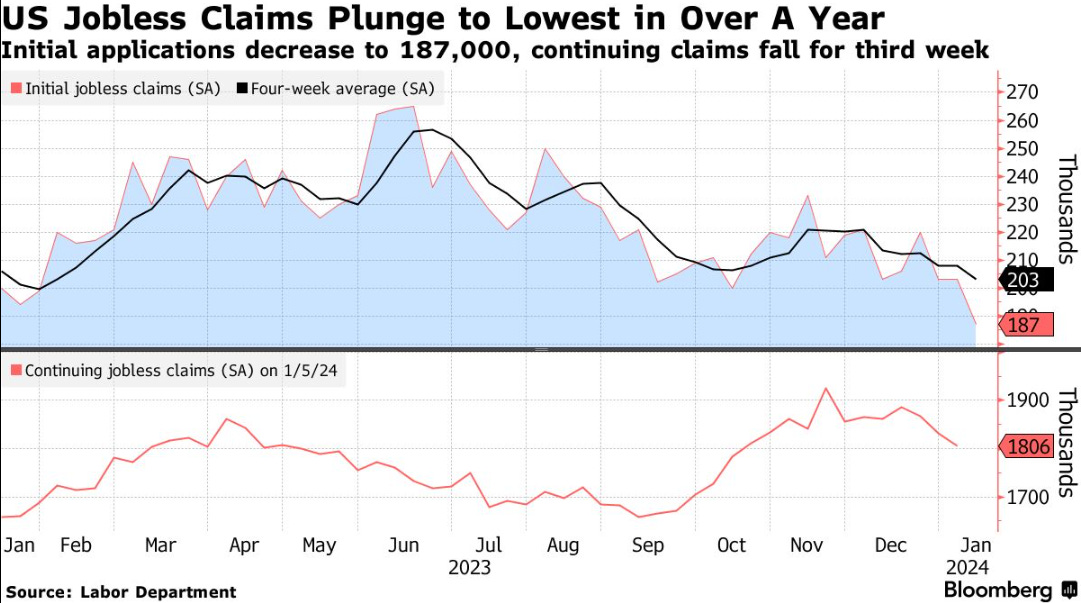

Initial jobless claims dropped below the 200K mark this week, and continuing claims remained in a downtrend for the third week in a row. While some of the recent decline in claims can be explained by seasonal factors, the multi-week moving averages continue to point to a strong labor market.

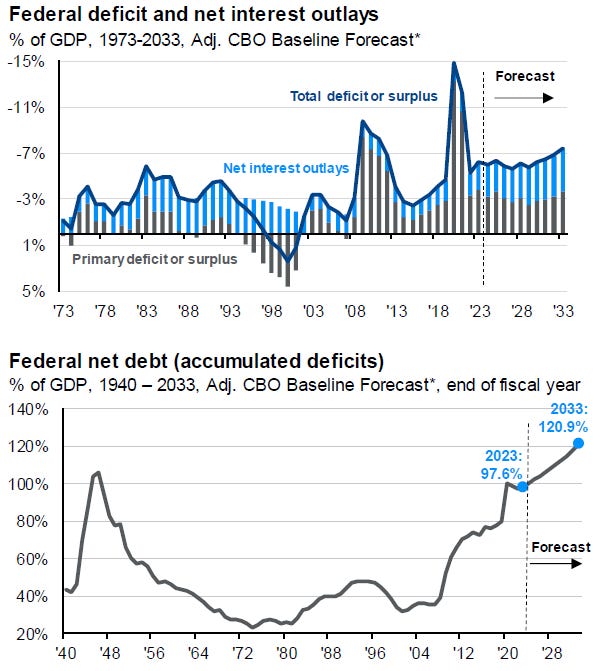

It’s hard to explain how the economy has continued to be this resilient for this long. If I had to guess, I would say that market participants and economists have severely underestimated the impact of fiscal spending and overestimated the transmission rate for interest rate hikes. Very few investors have seen a rate hike cycle combined with fiscal spending of this magnitude, and therefore it has been hard for all of us to calibrate our minds and economic models to account for these factors accurately. Perhaps it’s impossible to get a recession when the government is running a deficit that’s 7-8% of GDP (which previously would be unheard of, outside of recessionary periods). And perhaps the current level of real rates is sustainable indefinitely because the r-star (natural rate of interest) has shifted higher.

One point about interest rates that often gets missed is that higher interest rates also have a stimulative impact on the economy: consumers, businesses and investors can earn a higher return on cash, and the higher interest paid by the government on its debt is recycled back into the economy to domestic holders of US treasuries.

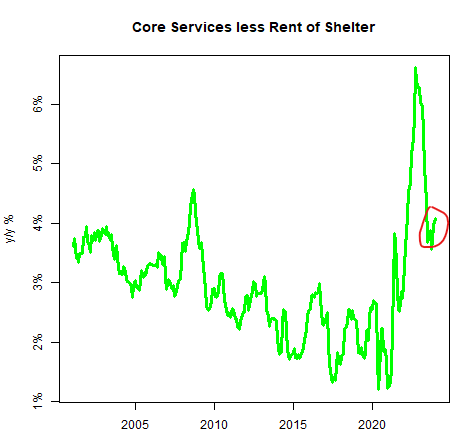

What about inflation? Maybe a sharp drop in inflation can bring us to the promised land of 6+ rate cuts this year? I discussed inflation risks in my macro outlook piece, but they are worth a quick refresher. While goods disinflation has started in earnest and shelter will continue to drag inflation lower in the coming months, core service inflation ex-shelter (i.e. the stickiest form of inflation that occurs in labor-intensive sectors) is showing some early signs of bucking the trend. This shouldn’t come as a surprise if you’ve been following the labor market.

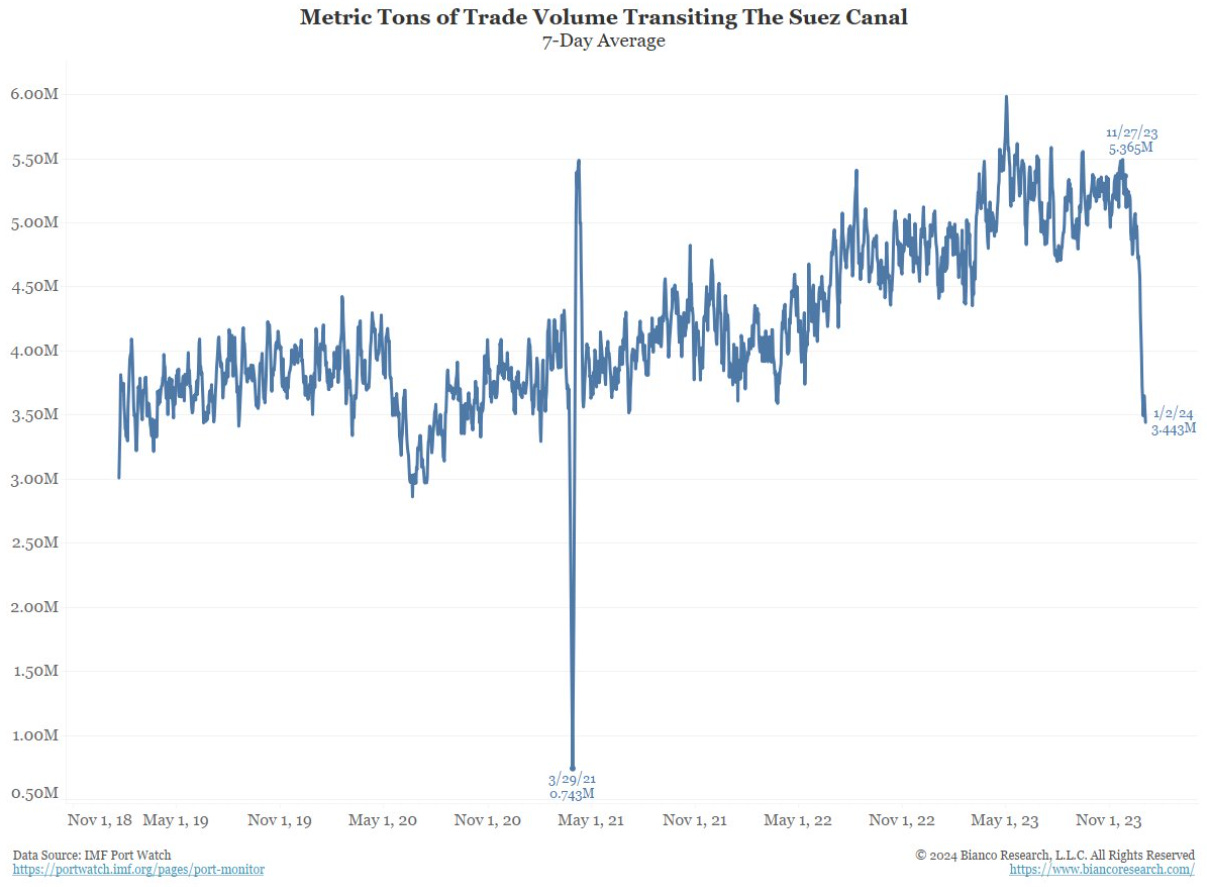

Goods disinflation may also be at risk due to recent supply chain issues. Two of the world’s largest shipping choke points (Suez Canal and Panama Canal) are continuing to operate at only half their capacity. You can argue these are ‘transitory’ factors, but anyone who’s been trying to forecast inflation over the past two years should approach this issue with a bit of humility.

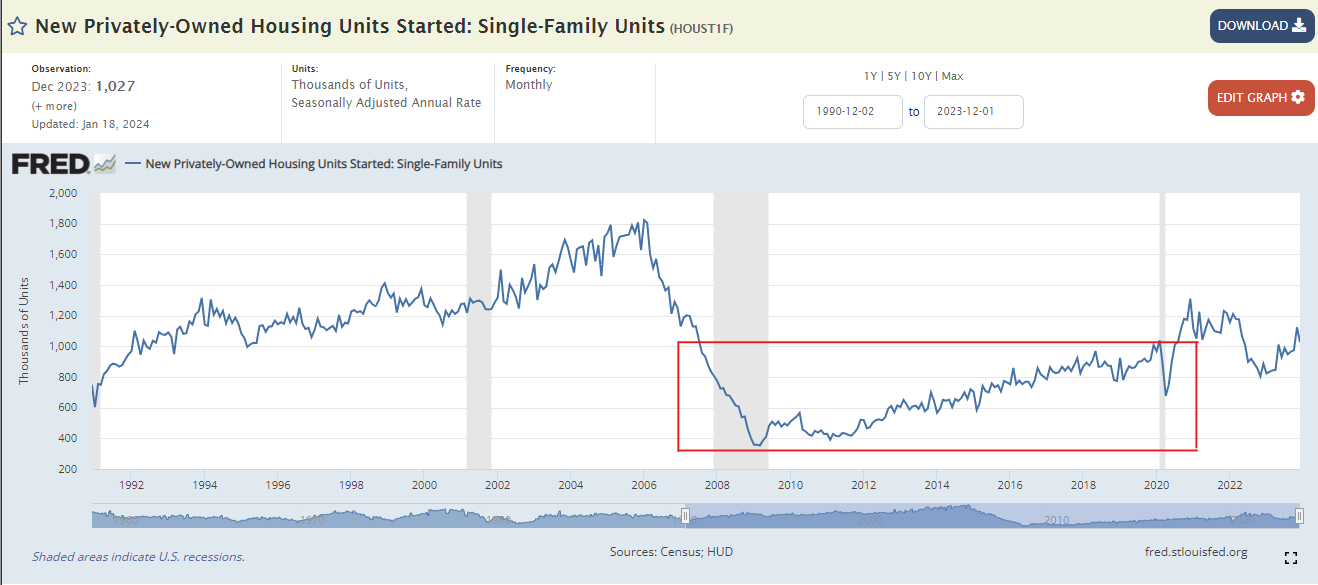

Rents will drag the CPI lower as rental growth slows, but there are limits to how much this can help the inflation picture. Rents won’t suddenly collapse, because the cost side for landlords hasn’t improved dramatically. The US is facing a housing shortage because of a combination of factors:

The post-GFC period witnessed significantly lower than average housing starts for several years (see chart below).

A big cohort of millennials are entering their prime home-buying years.

COVID accelerated inter-state migrations, so the current housing stock is not located in the right places (too many houses in California, NY, too few in Florida, Texas etc.).

This means that home prices and rents should resume an upward trajectory as interest rates come down. Longer-term pressures are skewed towards shelter inflation inflecting back higher, not lower.

The only 'structural’ force that could significantly alter the current macro picture and alleviate inflation risks is productivity growth. Unfortunately, productivity is incredibly hard to forecast as it depends on several complex factors such as societal / cultural changes, technological advancements, government policy etc.

Summary

The Fed’s signaling of rate cuts is not intended to ease monetary policy, but rather to maintain the current level of restrictiveness by keeping real interest rates stable.

Investors are using past cycles to forecast aggressive rate cuts, but this cycle is different for many reasons, including the significant impact of deficit spending, the structural tightness in the labor market, and the muted pass-through effect of higher interest rates.

The Fed is unlikely to change this policy until the economy weakens, or inflation drops rapidly.

Based on recent data, economic weakness is unlikely in the near term.

Inflation risks remain a coin toss, and it’s dangerous to assume that the current ‘immaculate disinflation’ will continue without hiccups.

This makes markets vulnerable. Downside protection / implied volatility is relatively cheap, and investors should take advantage.