There are three main components to the copper supply cycle:

Mines that produce copper ore, which is then processed to produce copper concentrate (20-40% copper content).

Smelters which further process copper concentrate into refined copper in the form of copper cathodes.

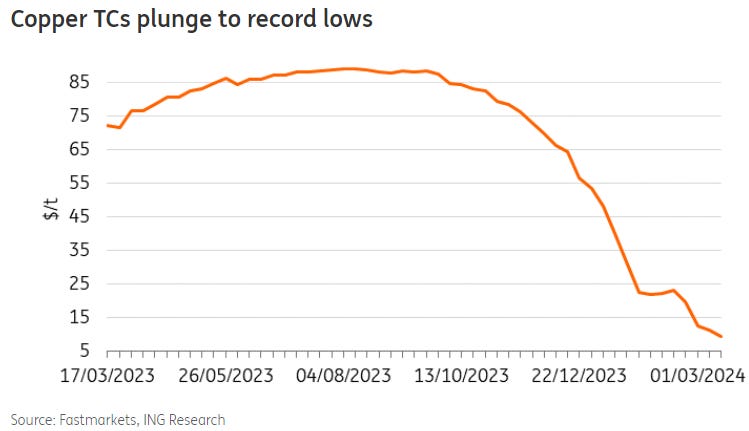

Smelters buy copper concentrate at a discount to be compensated for their services. This is commonly referred to as ‘treatment and refining charges’ or ‘TC/ICs’. These discounts are negotiated between the miners and smelters.

TC/ICs vary depending on the tightness of the copper concentrate market and smelter capacity. For example, if the concentrate market is tight, and there is abundant smelter capacity, then TC/ICs will drop.

Manufacturers that use copper cathode to manufacture the end product: copper wire rods, flat bars, pipes, sheets etc.

In this piece, I will be focusing mostly on the mining side, as that is where the primary supply bottleneck exists, and where I believe there are investment opportunities in companies that are able to successfully maintain and grow production to take advantage of a rising price environment.

On the smelting side, there has been a rapid expansion in refining capacities in China, driven by China’s strategic need for copper for the green energy sector. As a result, China now owns 80% of the world refining capacity, however it only mines 10% of copper concentrate. This makes China heavily dependent on countries like Chile, which are responsible for 30% of the world’s copper supply.

Smelting units / refineries require billions of dollars of investment, which means China has an insatiable appetite for copper to keep its smelters running at a high utilization rate, and ensure the investments earn an adequate return. However, all this refining capacity can also lead to an excess supply of refined product, and a supply/demand mismatch when smelting capacity exceeds the availability of copper concentrates. This has played out recently, with TC/ICs dropping to record lows due to mining disruptions and dwindling cathode inventories. In response, Chinese smelters agreed to a historic production cut earlier this year.

At the current TC/ICs of <$20, 70% of global smelting capacity is loss making, which means supply of refined copper should drop significantly going forward. In H2 2023, refined copper production growth far outweighed copper mine production growth, suggesting that smelters took advantage of attractive TC/ICs to draw down inventories.

The production of copper ore and concentrate is a long-cycle investment, similar to uranium. It takes 2-3 years to extend the life of existing mines, and 8+ years to establish new greenfield projects. Cost overruns, operational disruptions and regulatory delays are common. For example Teck’s Quebrada Blanca project was originally budgeted at $4.7bn around 4 years ago, but will actually cost around $8.6bn to complete. This is an extreme example, as the mine was originally conceived right before the COVID years, but rising cash costs are an industry-wide issue. Rising royalty rates, labor shortages, supply chain issues, weather/droughts (copper production is water intensive) and general inflation have impacted copper miners, just like the rest of the mining sector.

Copper is also highly exposed to geopolitical risks. Since 2022, Peru, the second-largest producer, has been rocked by political turmoil with almost 30% of the country’s mining supply at risk. Glencore’s Antapaccay and MMG’s Las Bamba in Peru, which account for 2.5% of global supply, experienced shut downs in response to rioting. In Chile, the world’s largest copper supplier, the leftist government of Gabriel Boric has been in favor of increased state involvement in the mining sector, and imposing higher taxes and royalties. This has put mining companies who were looking to invest in Chile on high alert. Chile’s production has been stagnating due to deteriorating ore grades, water scarcity and increase in permitting timelines. The state copper miner, Codelco, is struggling to return production to pre-COVID levels.

In November last year, the Supreme Court of Panama ruled that the Government’s contract with First Quantum Minerals (FQM), a Canadian mining company, was illegal. The court claimed that FQM had not taken into consideration the threats to Panama’s rainforest, animal habitats and waterways resulting from its mining operations. In December, the Panama Government ordered FQM’s Cobre Panama mine, which represents 1.5% of global copper supply, to be shut down. Given that the mine represents almost 5% of Panama’s GDP and employs nearly 7000 domestic workers, many believe that the mine closure is temporary, and that FQM will be allowed to operate after paying penalties and/or negotiating higher royalties. However, this incident is a stark reminder of the fragility of copper supply chain.

Apart from geopolitical risks, copper supplies all over the world have consistently been revised down for other reasons such as geotechnical issues, equipment failures, weather, landslides and declining ore grades. Most notably, Anglo American downgraded its 2024 production forecast by 0.73-0.79Mt due to logistical and operational issues, which may be linked to declining ore quality.

While a number of new copper mines have come online recently (DRC’s Kamoa-Kakula, Quellaveco in Peru, Quebrada Blanca II and Spence-SGO in Chile), boosting production by ~0.75Mt, this new production has been offset by the aforementioned issues at existing mines. The net result is that supply estimates have been downgraded significantly, and are now well below refined global consumption estimates for the next couple of years.

This is not a problem that is expected to be resolved anytime soon. After the latest cohort of large mines that came online in 2023, the supply increase from new projects will decline drastically in the coming years due to the dearth of greenfield projects.

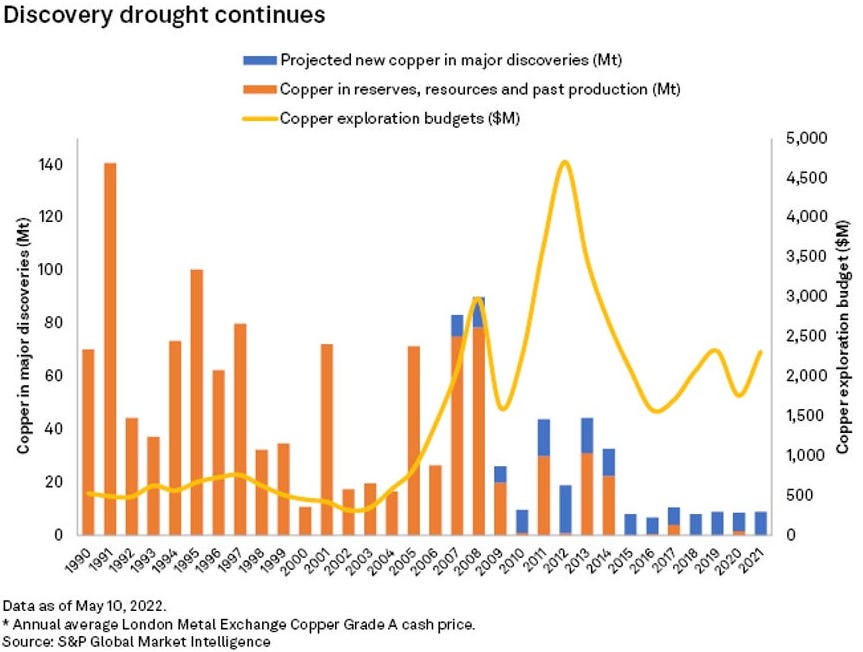

After the last commodity bull cycle, which ended with the global financial crisis, growth and exploration budgets for copper dropped dramatically, and have stayed depressed. As a result, new copper discoveries are at historic lows, and the pipeline of new projects has dried up.

Additionally, some of the discoveries that are being made today in countries like Canada and the US have very onerous permitting requirements and timelines. For example, the Resolution copper deposit in Arizona was discovered 30 years ago, and is yet to be permitted. In North America it can take on average 20 years to build a copper mine, from exploration success to the first copper concentrate being poured. Therefore, even if a massive deposit was discovered today, it may not get built until the 2040s.

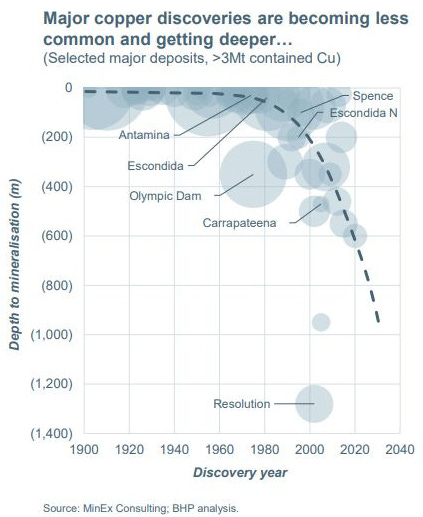

Compounding the lack of exploration and growth capex is the fact that copper mines are becoming deeper and more complex, leading to higher exploration, development capex and operational risks.

Ore grades have also been declining. By 2030, copper ore grades are expected to be only 25% of their 1990 levels. This means more material has to be removed / transported / refined to produce the same quantity of refined copper.

A good example of the challenges facing new copper deposits is the Filo del Sol deposit discovered recently by Filo Mining in Argentina. The deposit is located deep under the rock surface in the Andes Mountain range in Argentina, in a very remote region. Infrastructure is non-existent, and logistics for transportation will be expensive and complex, as the refined material has to be taken from a high elevation above sea level, to a port. While there is speculation that this could be a generational resource, the capital costs to build the mining camp are expected to be as high as $8 - $10bn.

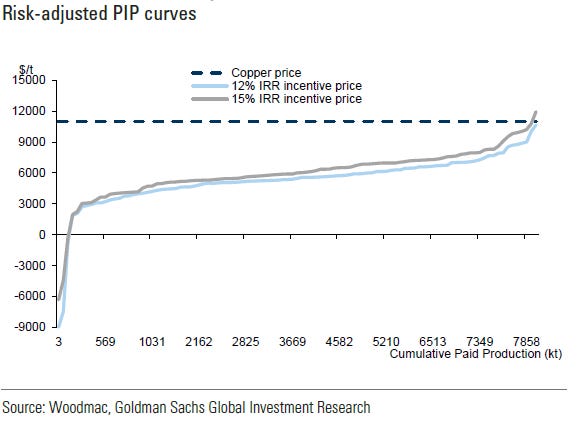

Due to all these factors, historical copper prices and cost curves have to be adjusted higher when formulating today’s incentive price. Based on the latest cost curves I’ve seen from industry consultants, copper prices would need to be sustained above $10K/t or $4.5/lb to incentivize sufficient greenfield projects to mitigate the incoming supply gap.

New mines are also likely to receive more ESG pushback, as the energy intensity and environmental impacts of copper mining are likely to increase significantly. Ultimately, the ESG crowd will have to face the reality that they can’t have it both ways: they can’t dream of electrification and zero emissions, without the intense energy usage and emissions released from the mining of large quantities of metals like copper from increasingly scare and hard to access deposits.

Lastly, we have to look at inventory levels. Inventory buffers for the market have been diminishing over the past few years. In 2023, despite strong demand and supply disruptions, bulls continued to be frustrated as inventory draw downs capped prices. In the DRC, almost 13K tonnes of copper had been stuck for over nine months at the Tenke Fungurume mine, due to a dispute over royalties between CMOC (a Chinese mining company) and the DRC’s state mining company, Gecamines. The export ban was finally lifted in June last year, freeing up the equivalent of 7% of global copper production.

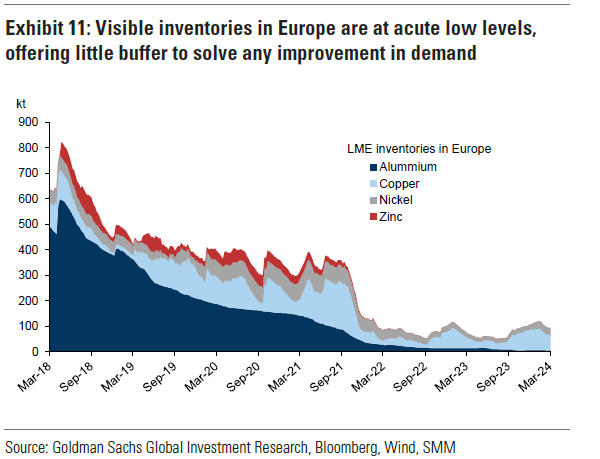

Global cathode levels are now well below the 6 year range. This is similar to the de-stocking we’ve seen in oil and petroleum products in the post-COVID era, and can partially be explained by the higher interest rate environment, which makes commodity storage a lot more costly.

European inventories in particular are at acutely low levels, and any turnaround in the economy and manufacturing activity would lead to a sharp demand impulse.

As the year progresses, the major variables influencing copper prices will be the potential restart of Cobre Panama, any further supply disruptions, and whether the recent positive trends in global manufacturing and economic growth can hold up. In the absence of a negative demand shock, the market is expected to be in a deficit that will put upward pressure on prices, especially in light of the lower inventory buffers. Over the longer-term, given the current trends in supply, the world will struggle to meet the 5-7Mt of demand growth expected over the course of this decade, resulting in a higher-for-longer price environment.

Conclusion

Copper is a long-cycle commodity with 8-10 years needed to build new mines. In Western markets, tough permitting guidelines and ESG constraints can lead to even longer lead times, making many new projects prohibitively expensive.

Almost half of copper production today comes from politically unstable regions, making supply disruptions frequent.

After the last commodity cycle, miners have cut back on growth capex, and new copper discoveries are at historic lows.

The latest copper projects have lower ore grades and are deeper underground, resulting in higher cost, operational risks and energy intensity.

Existing mines are struggling to maintain and grow production due to inflation, reserves depletion and political uncertainties.

After a big production growth spurt in 2022 and 2023 (~12% increase in global production) as a result of new mines coming online, supply growth is expected to slow significantly due to a dearth of new projects.

In the near term (~1 year), prices will be subject to Chinese economic outlook and green investment demand, global manufacturing/macro and potential restart of Cobre Panama; over the longer term, in order to meet emissions and electrification objectives, prices will have to sustain at >$10K/t or $4.5/lb to incentivize sufficient new projects.