Bubble Trouble

Identifying a bubble can be a lot easier than trading or investing through one

It’s a platitude to say that markets move in cycles. The harder part is identifying whether we’re closer to a top vs. a bottom, and being able to successfully trade and / or invest through changing market conditions.

Until recently, most investors were of the view that the rally in tech stocks would continue and that traditional valuation metrics focused on profitability and cash flows didn’t matter anymore. And who could blame them? The past 10+ years have been a resounding success for growth investing.

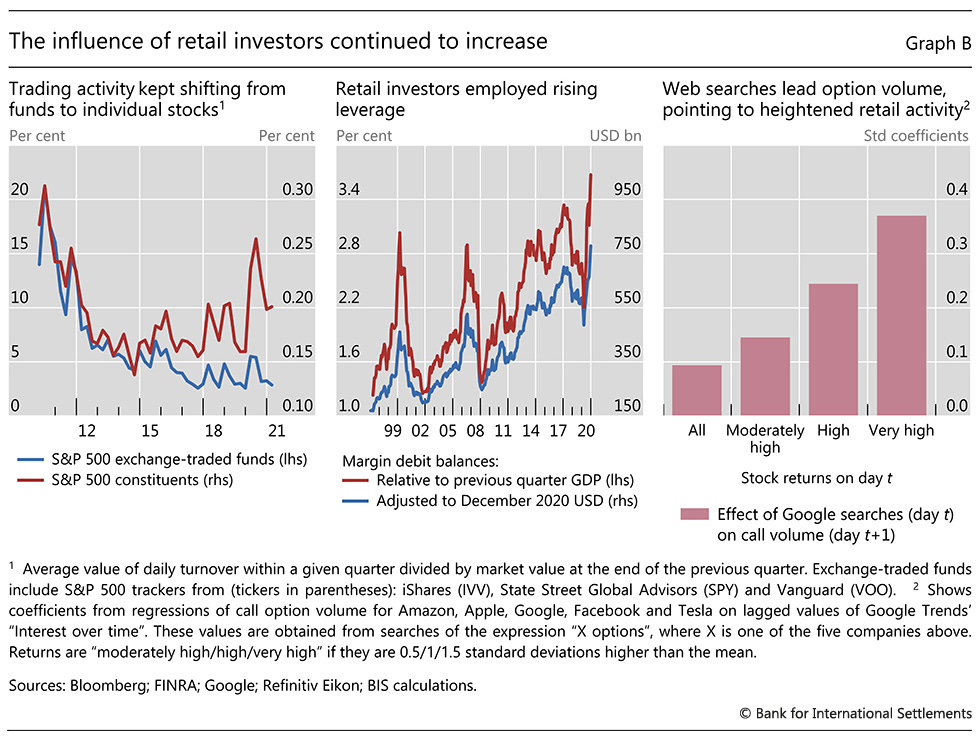

The COVID-19 crisis ushered in an era of new extremes in speculative activity. Investors became increasingly inclined to jump on to the latest growth, fad or meme stock without doing the prerequisite fundamental work on valuations, financial performance and business quality. Retail investor participation in the stock market increased significantly, reminiscent of the dot com era.

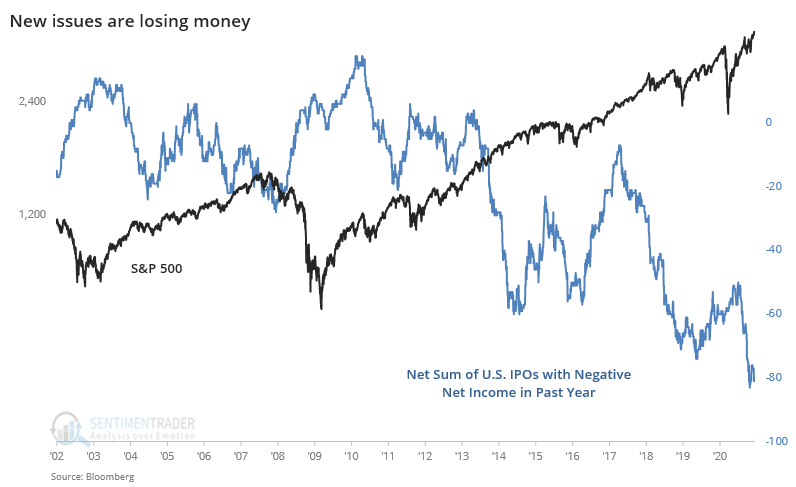

Meanwhile Wall Street obliged by supplying record volumes of money-losing IPOs.

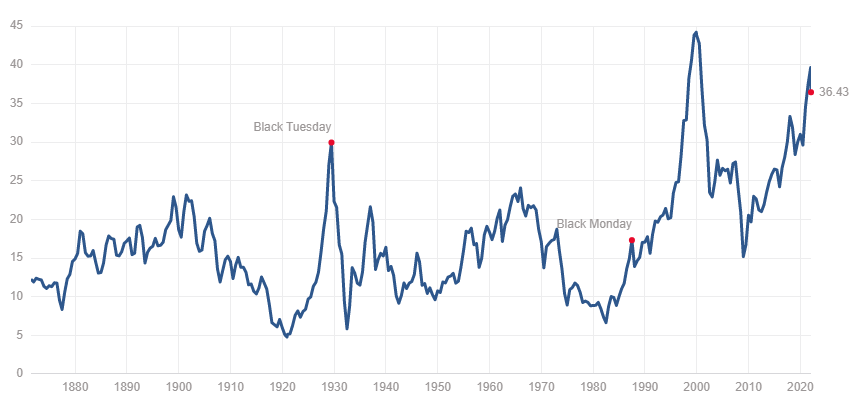

It’s easy to look at the recent sell off and talk about how ‘obvious’ the signs were or posit that shorting tech stocks was a ‘no-brainer’. But the reality is that you could have made the same arguments all throughout 2020 and 2021. Some would argue that the market has been over-valued for much longer, given the consistently rising valuation multiples post the 2008 Great Financial Crisis.

In a note last week Sean Kammann, portfolio manager at Wellington Managment, commented on the historical uniqueness of recent market trends [bolding mine]:

“What’s important to realize is how unusual 2020 and the decade before that was…From 1927 to 2020, value outperformed growth by 397 basis points annually on average. For the rolling 10-year periods from 1936 to 2020, value outperformed 91% or 85% of the time (depending on how you measure it). Perhaps even more interestingly, almost all of those rolling 10-year periods where growth outperformed were 10-year periods that ended in the last decade. What we have just witnessed, and what many investors globally likely anchor to, is extraordinarily unusual.”

So what is a value investor to do during such a prolonged period of market dislocation?

I think there are four main options: 1/ you can try and probe against the bubble by going short 2/ you can stick to your investment principles and framework, waiting for the market conditions to change and reward your investments in the long run 3/ you can succumb to the pressure and participate in the bubble 4/ you can leave the game for a period of time.

All of these options sound reasonable in theory, but are hard to implement in practice.

Shorting requires being accurate on timing as it is a negative carry trade (due to the cost of borrow + dividends) with strict margin requirements due to it’s asymmetric nature (losses can be infinite while gains are limited to a stock price of zero). Even legendary short sellers like Jim Chanos and David Einhorn have found the current environment unforgiving.

Sticking to a value investing strategy for the long run sounds simple, but investors will eventually grow impatient and start questioning your strategy if you continuously underperform the markets. They may start pressuring you to change course or return their money. A lot of value investment funds have closed doors in the last couple of years under such pressures.

If you choose to participate in the bubble, you’ll be doing something completely different from what your mind is hard-wired to do. The big challenge with ‘trading’ a bubble is figuring out when to sell. When stock prices are disconnected from fundamentals and trading based on investor sentiment, the only way to realize profits is by selling to a ‘greater fool’. As the last few months have reminded us, sentiment can be a fickle thing and reverse violently. When the greater fool disappears, you are suddenly stuck holding the bag.

To avoid this situation you must expand your skillset beyond pure fundamental analysis to include an understanding of market structure, liquidity, sentiment, technical analysis and the use of trading-based risk management tools such as stop loss orders (amongst others).

Perhaps the biggest danger of participating in a bubble is that in the process you may end up fooling your investors, and ultimately yourself, into thinking that what you’re buying is justifiable based on fundamentals / valuation. A great example of this is fund managers using asinine valuation metrics like price-to-sales, EV / TAM (Enterprise Value / Total Addressable Market) or EV / 20[25] EBITDA multiples to justify their ‘investments’. With a number of these investments now cut in half and the businesses still losing prodigious amounts of money every year, it’s unclear where the bottom is. I’m already seeing a number of investors / fund managers double down on their mistake by labelling growth stocks ‘cheap’ because they are trading at only 10x sales now vs. 20x sales a few months ago.

That leaves us with the last option, quitting the game all together for a period of time. Some of the greatest investors like Warren Buffett have gone down this path. More than 50 years ago, Buffett closed down his partnership and returned his investors’ money citing a dearth of investment opportunities. In his 1967 letter he warned of "speculation on an increasing scale" and admitted that he was “out of step” with the market conditions at the time.

The difficulty here is that if you’re a full-time investor it’s incredibly hard to give up your day job and find another means of sustenance; especially when you have no idea how long the bubble could last. Even harder is the psychological challenge of staying on the sidelines while your peers are getting wealthier year after year.

Realistically one probably needs to experiment with and execute a combination of these strategies to be successful. The one thing you can’t do is refuse to evolve and stubbornly stick to one style of investing in the hopes that the market will eventually start to ‘make sense’. As the last few years have made it abundantly clear, the market doesn’t have to do anything, and it certainly doesn’t care what you or I think it should do. Yes, valuations matter in the long run. But the long run can be longer than you think.