Advanced Nuclear

How small modular reactors (SMRs) can transform the energy landscape and the uranium market

Conventional nuclear power plant construction is a massive undertaking with little standardization. Almost every plant is custom built / “first of its kind” and has to adhere to complex and constantly changing regulatory requirements. As a result, nuclear power projects have developed a reputation for poor project management, cost over runs and construction delays. This is probably the most important, valid criticism against deploying nuclear energy at scale.

In the US alone there are dozens of different reactor designs in use currently. A great example is Arkansas Nuclear One, a two unit nuclear power plant where each unit uses a completely different design (one supplied by Babcock & Wilcox and the other by Combustion Engineering), despite being situated right next to each other. Conventional nuclear projects are also tricky to finance given the large sums of money required upfront in exchange for an uncertain and risky payout timeline. A notable example is the default of Washington Public Power Supply System (WPSS) bonds issued to finance two nuclear power plants in the early 1980s that were canceled.

To overcome these obstacles, scientists have been working on a new generation of reactors (Small Modular Reactors or SMRs) that are smaller (up to 300 MWe per unit), simpler to build and have a modular design, making it possible for systems and components to be factory-assembled and transported as a unit to a location for installation. These reactors are also being designed with better safety features (passive systems, low operating pressures) which don’t require human intervention in the case of an emergency, and nearly eliminate the potential for unsafe releases of radioactivity.

Investors and governments have recognized the opportunity in SMRs with development efforts accelerating in recent years. There are currently more than 70 commercial SMR designs in development worldwide, including backing from big names like Bill Gates. Some of the major companies involved in SMR development include GE, Rolls Royce, Babcock & Wilcox, NuScale and Terrapower. The idea is also gaining traction with potential corporate customers - some recent examples include Nucor, Dow Inc. and Canadian Oil sector. The IAEA expects 100+ SMRs to be in deployment worldwide by 2030.

The significance of SMRs to the nuclear fuel cycle and uranium prices is hard to overstate. Most SMRs will require High Assay Low Enriched Uranium (HALEU), where the U-235 isotope is enriched to above 5% required for conventional reactors; but the only supplier capable of delivering HALEU at present is a subsidiary of the Russian company Rosatom.

I’ve talked about uranium market bi-furcation numerous times on this blog - but here is yet another example of why the demand impulse for Western enriched uranium could skyrocket in the coming years: the number 1 issue for advanced reactor developers and their customers right now is fuel sourcing / availability. The US Department of Energy (DOE) announced an RFP in June to acquire HALEU supply chain services to kick-start the process of in-sourcing HALEU production. Below are some important excerpts from their statement:

The U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) is seeking feedback on two draft requests for proposals (RFPs) to acquire high-assay low-enriched uranium (HALEU)—a crucial material needed to develop and deploy advanced reactors in the United States.

“We must jump-start a commercial-scale, domestic supply chain for HALEU,” said Dr. Kathryn Huff, Assistant Secretary for Nuclear Energy. “Acquiring these services in the United States will reduce reliance on Russia, create American jobs, and support U.S. climate and energy security goals.”

DOE projects that more than 40 metric tons of HALEU could be needed before the end of the decade, with additional amounts required each year, to deploy a new fleet of advanced reactors in a timeframe that supports the Biden-Harris Administration’s goal of 100% clean electricity by 2035.

Let’s step back and think about what this means for the uranium market:

The market is currently in structural deficit with utility inventories dwindling and replacement rate contracting beginning to take place this year

Adding to the structural deficit is the switch from under to overfeeding, reactor life extensions and financial demand (SPUT, Zuri Invest, Yellow Cake and several other vehicles in process of being set up such ANU Energy)

On top of this, SMRs are rapidly evolving from concept to reality but are still not included in many supply / demand models; if we just take the IAEA’s projection of 100 SMRs by 2030 and assume each SMR is 300MW, that’s an additional 12mm lbs of yearly demand (assuming ~400K lbs of demand annually per 1 GW)

SMRs are also designed to run on significantly elongated refueling cycles vs. conventional plants. While conventional plants typically require 2-3 fuel loadings upfront, most SMR designs require 10 or 20 years of fuel up front

If the initial SMR developments are successful, the number of SMRs is likely to grow much larger than 100 given the desperate need for green energy to fuel global growth and for new technologies like AI. The below excerpt from an interview with the University of Pennsylvania’s Deep Jariwala caught my attention (emphasis mine):

“We take it for granted, but all the tasks our machines perform are transactions between memory and processors, and each of these transactions requires energy. As these tasks become more elaborate and data-intensive, two things begin to scale up exponentially: the need for more memory storage and the need for more energy.

Regarding memory, an estimate from the Semiconductor Research Corporation, a consortium of all the major semiconductor companies, posits that if we continue to scale data at this rate, which is stored on memory made from silicon, we will outpace the global amount of silicon produced every year. So, pretty soon we will hit a wall where our silicon supply chains won’t be able to keep up with the amount of data being generated.

Couple this with the fact that in 2018 our computers consumed roughly 1-2% of the global electricity supply, and in 2020, this figure was estimated to be around 4–6%. If we continue at this rate, by 2030, it's projected to rise between 8-21%, further exacerbating the current energy crisis.”

All these factors further enhance the bull thesis for uranium. While 2030 may seem ages away for the first wave of SMR deployments, it’s imminent in terms of the nuclear fuel cycle. If you’ve been following my writing on this topic, you know that new uranium mines often take 10 years or more from discovery to production, and that once uranium is mined it needs to be converted, enriched, fabricated before it can enter a reactor (a process that start to finish often takes up to two years). In other words if you want uranium for 2030, you should start thinking about it before 2020.

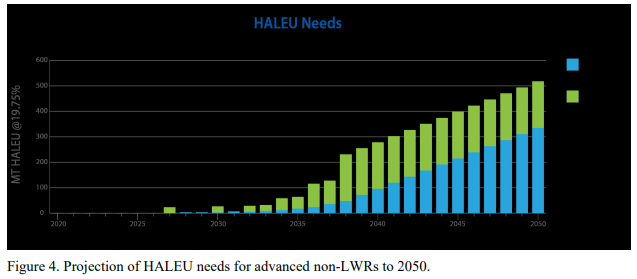

Long term forecasts are always difficult and usually wrong, but it’s still worth noting that Idaho National Lab’s energy analysis team (that conducts research for the DOE) built a model projecting 500MT of HALEU demand per year coming from SMRs by 2050, for the US alone. This would mean a doubling of the current US uranium demand. I’ll leave it to your imagination what that means for uranium prices.

Conclusion

I believe SMRs can solve many of the world’s energy problems by providing reliable, baseload, carbon-free power to the grid in a cost-effective manner, something that renewables have promised but failed to deliver. Given the flexibility afforded by their smaller size, SMRs can be deployed not only in cities, but also at industrial sites or remote areas with limited grid capacity and for various applications including power, heating, water desalination, industrial steam etc.

However if SMRs are to be deployed at scale, we need a much larger supply of uranium, which will only be possible through higher uranium prices and government incentives. Given the significant underinvestment in uranium production over the last decade and the length of the fuel cycle, it may already be too late. Under the current scenario, we’ll likely have a situation where utilities, SMR developers/ customers, governments and financial players will all be competing to secure uranium and there simply won’t be enough for everyone.

Because SMR deployments are still 5+ years away, and because the history of nuclear power development is rife with delays, cost over runs and outright failure, there is still a fair amount of skepticism regarding SMRs in the mainstream media and amongst investors. However if the technology continues to mature at the current rate, the nuclear fuel cycle will start experiencing its effects soon.